Walter Wink |

- Wikipedia -

|

Walter Wink (May 21, 1935 – May 10, 2012) was an American Biblical scholar, theologian, and activist who was an important figure in Progressive Christianity. Wink spent much of his career teaching at Auburn Theological Seminary in New York City. He was well known for his advocacy of and work related to nonviolent resistance and his seminal works on "The Powers", Naming the Powers (1984), Unmasking the Powers (1986), Engaging the Powers (1992), When the Powers Fall (1998), and The Powers that Be (1999), all of them commentaries on the Apostle Paul's ethic of spiritual warfare.

Alistair McIntosh Files

Alistair McIntosh Files

May 2, 2023: Insights:THE INFLUENCE AND IMPACT OF WALTER WINK’S ENGAGING THE POWERS

Scottish activist and Quaker, Alistair McIntosh, writes in Engaging Walter Wink’s Powers – An Activist’s Testimony that one of the most important things that transformed him from teenage agnostic activist was encountering Wink’s works while at a Quaker and Iona Community event at Peace House led by Helen Steven. Wink’s work, she believed, “was of profound importance to activism, and especially nonviolent activism, because it took the understanding of power into realms deeper than she had ever previously encountered in theological writing.” Wink also offered a practical formula for activist application:

1) Name the Powers. . . finding the courage to break silence and simply state the abuse of power.

2) Unmask the Powers . . . revealing the social, economic, psychological, and spiritual dynamics by which they oppress.

3) Engage the Powers—wrestling so as not to destroy them—not to take life—but rather, to call them back to their higher, God-given calling.

This model has continued to be taught by Wink and others since the 1980’s as a life-affirming and proactive way of resisting the Powers in the world. McIntosh uses Engaging the Powers as a text for Spiritual Activism classes at Strathclyde University in Scotland. He also gives a number of practical examples where he utilised the model for successful outcomes including land reforms in Scotland, resisting environmentally damaging mining in Papua New Guinea and Scotland, explaining non-violence to military officers and exposing the destructive nature of cigarette advertising.

Scottish activist and Quaker, Alistair McIntosh, writes in Engaging Walter Wink’s Powers – An Activist’s Testimony that one of the most important things that transformed him from teenage agnostic activist was encountering Wink’s works while at a Quaker and Iona Community event at Peace House led by Helen Steven. Wink’s work, she believed, “was of profound importance to activism, and especially nonviolent activism, because it took the understanding of power into realms deeper than she had ever previously encountered in theological writing.” Wink also offered a practical formula for activist application:

1) Name the Powers. . . finding the courage to break silence and simply state the abuse of power.

2) Unmask the Powers . . . revealing the social, economic, psychological, and spiritual dynamics by which they oppress.

3) Engage the Powers—wrestling so as not to destroy them—not to take life—but rather, to call them back to their higher, God-given calling.

This model has continued to be taught by Wink and others since the 1980’s as a life-affirming and proactive way of resisting the Powers in the world. McIntosh uses Engaging the Powers as a text for Spiritual Activism classes at Strathclyde University in Scotland. He also gives a number of practical examples where he utilised the model for successful outcomes including land reforms in Scotland, resisting environmentally damaging mining in Papua New Guinea and Scotland, explaining non-violence to military officers and exposing the destructive nature of cigarette advertising.

Ken Butigan Files

Ken Butigan Files

May 17, 2012: Waging Nonviolence: How Walter Wink confronted violence

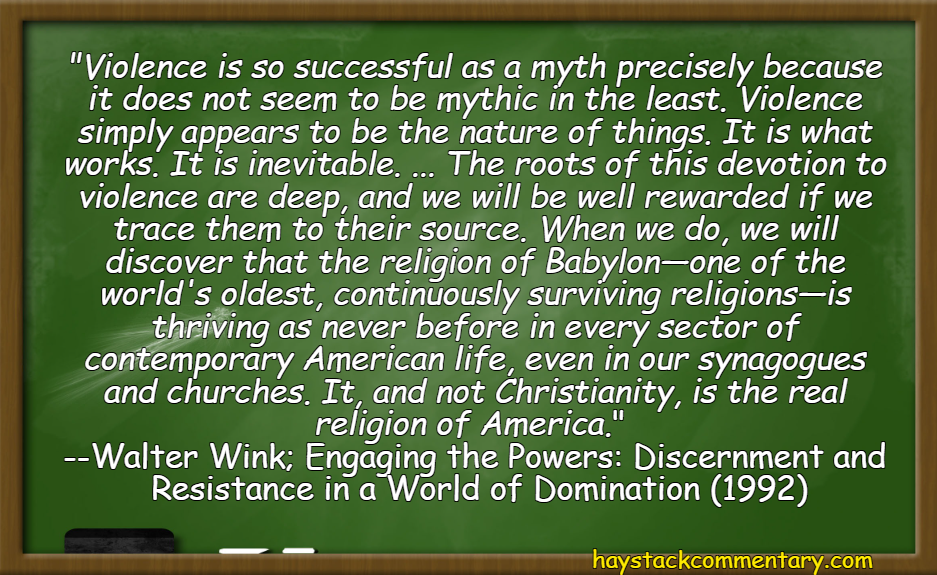

The contemporary epidemic of violence stems from our acknowledged or unacknowledged belief that violence ultimately is just and necessary. Wink named this “the myth of redemptive violence.” This myth — in the sense of the foundational story by which we live — permeates our consciousness and our culture. Hence our age’s greatest temptation: to cling to a belief in the effectiveness and preeminence of violence, the conviction that it is “the bottom line,” that violence is the final answer.

For Wink, nonviolent resistance is a critically important process for challenging violence, but, even more deeply, it is an embodied practice that can help to free us from our faith in violence forged in the furnaces of fear, hate, greed, ambition, resignation and capitulation. Creating nonviolent alternatives is a spiritual practice and a way of being at the service of the transformation of our selves, our communities and our world.

For Wink, this vision did not come from abstract speculation. Instead, it flowed from his wrestling with the Christian Gospels. For two thousand years, these accounts of the life and work of Jesus have nourished the convictions of a handful of peace churches like the Bretheren, the Anabaptists and the Quakers, but the vast majority of the Christian tradition have, willfully or not, watered down or stifled the message of radical nonviolence. Like a series of 20th-century scholars — including Andre Trocme, John Howard Yoder, Howard Thurman, Roland Bainton, Ched Myers, and John Dominic Crossan — Wink was unsatisfied with the centuries-old take that had muffled the nonviolent Jesus and that had left much of Christianity colluding with systems of violence, including theological justifications of war. So he turned his exegetical skill on the Gospels to see what they would reveal.

He did this in many ways, but one of the most memorable — and likely far-reaching — was his interpretation of Jesus’ saying to “turn the other cheek” and other sayings in the Gospel of Matthew:

You have heard that it was said, “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” But I say to you, Do not resist one who is evil. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also; and if anyone would sue you and take your coat, let him have your cloak as well; and if any one forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles. (Matthew 5:38-41, Revised Standard Version)

These exhortations has been used for 2,000 years to breed submission and complicity, especially since they were linked in the same passage to the admonition: “Do not resist an evildoer.” Wink began his research by wondering about this phrase. When he went back to the Greek text, he found that the original meaning was quite different. While the verb antistenai has been almost universally translated as “resist,” it is in fact a military term that means “resist violently or lethally.” Rather than encouraging passivity, Jesus was saying, “Don’t be a doormat. Resist violence, but not with retaliatory violence.”

The contemporary epidemic of violence stems from our acknowledged or unacknowledged belief that violence ultimately is just and necessary. Wink named this “the myth of redemptive violence.” This myth — in the sense of the foundational story by which we live — permeates our consciousness and our culture. Hence our age’s greatest temptation: to cling to a belief in the effectiveness and preeminence of violence, the conviction that it is “the bottom line,” that violence is the final answer.

For Wink, nonviolent resistance is a critically important process for challenging violence, but, even more deeply, it is an embodied practice that can help to free us from our faith in violence forged in the furnaces of fear, hate, greed, ambition, resignation and capitulation. Creating nonviolent alternatives is a spiritual practice and a way of being at the service of the transformation of our selves, our communities and our world.

For Wink, this vision did not come from abstract speculation. Instead, it flowed from his wrestling with the Christian Gospels. For two thousand years, these accounts of the life and work of Jesus have nourished the convictions of a handful of peace churches like the Bretheren, the Anabaptists and the Quakers, but the vast majority of the Christian tradition have, willfully or not, watered down or stifled the message of radical nonviolence. Like a series of 20th-century scholars — including Andre Trocme, John Howard Yoder, Howard Thurman, Roland Bainton, Ched Myers, and John Dominic Crossan — Wink was unsatisfied with the centuries-old take that had muffled the nonviolent Jesus and that had left much of Christianity colluding with systems of violence, including theological justifications of war. So he turned his exegetical skill on the Gospels to see what they would reveal.

He did this in many ways, but one of the most memorable — and likely far-reaching — was his interpretation of Jesus’ saying to “turn the other cheek” and other sayings in the Gospel of Matthew:

You have heard that it was said, “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” But I say to you, Do not resist one who is evil. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also; and if anyone would sue you and take your coat, let him have your cloak as well; and if any one forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles. (Matthew 5:38-41, Revised Standard Version)

These exhortations has been used for 2,000 years to breed submission and complicity, especially since they were linked in the same passage to the admonition: “Do not resist an evildoer.” Wink began his research by wondering about this phrase. When he went back to the Greek text, he found that the original meaning was quite different. While the verb antistenai has been almost universally translated as “resist,” it is in fact a military term that means “resist violently or lethally.” Rather than encouraging passivity, Jesus was saying, “Don’t be a doormat. Resist violence, but not with retaliatory violence.”

Tim Grimsrud Files

Tim Grimsrud Files

Jan 3, 2018: Open Democracy: Transforming the powers: the continuing relevance of Walter Wink

Wink argues in Naming the Powers that the language of “Principalities and Powers” in the New Testament refers to human social dynamics—institutions, belief systems, traditions and the like. These dynamics, or what he calls “manifestations of power,” always have an inner and an outer aspect. “Every Power tends to have a visible pole, an outer form—be it a church, a nation, an economy—and an invisible pole, an inner spirit or driving force that animates, legitimates, and regulates its physical manifestation in the world. Neither pole is the cause of the other. Both come into existence together and cease to exist together.”

In Wink’s view, we need such an integrated, inner-outer awareness in order to understand the world we live in and act effectively as agents for healing and transformation. “Any attempt to transform a social system without addressing both its spirituality and its outer forms is doomed to failure,” as he puts it in Engaging the Powers. What's more, in Wink's understanding all systems of power have the potential to be just or unjust, violent or nonviolent. “The Powers are good. The Powers are fallen. The Powers must be redeemed.”

“We cannot affirm governments or universities or businesses to be good unless at the same time we recognize that they are fallen,” he continues “We cannot face their malignant intractability and oppressiveness unless we remember that they are simultaneously a part of God’s good creation. And reflection on their creation and fall will appear only to legitimate these Powers and blast hope for change unless we assert at the same time that these Powers can and must be redeemed.”

This cycle of personal and institutional redemption provides a pathway to deep social change, but Wink refuses to pit the political against the personal. If either side is missing, he insists, genuine transformation won’t be possible. To illustrate what this means in concrete terms, take his analysis of contemporary North America, which focuses on the role of violence in US culture. Wink challenges what he calls the “myth of redemptive violence”—the belief that violence saves, that war brings peace, and that might makes right. His work explores how to combat this myth and further a social order that is free from domination.

A major problem in American culture has long been the devotion of an incredible amount of resources to the military-industrial complex. As a consequence, the US projects force as a solution to conflict in ways that only heighten global insecurities through a constant stream of ‘blowbacks.’ These social dynamics are fueled in part by the socialization of Americans into a mentality that insists on responding to perceived enemies with fear and violence. Wink’s analysis helps us to see how our refusal to confront the darkness within ourselves on both the personal and the societal levels blinds us to alternative approaches to enmity that can lead to a growth in self-knowledge and open up pathways to reconciliation.

His thinking about “domination systems” helps us to understand the contemporary context of large-scale violence in America and beyond, a system that entraps us all in the amazingly self-destructive dynamic of violence responding to violence, and on and on and on in this same vein. And his analysis of the role that the Principalities and Powers play in human culture helps us to make sense of why our structures are so destructive of human wellbeing.

As another example, take the crises of climate change and environmental degradation. Thus far we have not found a way to wrest control of our economic systems away from the ideologies and institutions that are driving us over the cliff of irreversible and catastrophic ecological change. Something in these systems resists change—but it is also true that our personal addictions to wasteful lifestyles and our deference to political and corporate leaders render us largely impotent.

As these examples show, the inner or spiritual Powers are not separate heavenly or ethereal realities but rather the inner aspects of material or tangible manifestations of power in relation to nature—as well, we may note, in relation to prisons, the police, racial and sexual violence, debates over gun control, militarism and the ‘War on Terror.’ As Wink writes in Naming the Powers:

“The ‘principalities and powers’ are the inner or spiritual essence, or gestalt, of an institution or system. The ‘demons’ are the psychic or spiritual power emanated by organizations or individuals or subaspects of individuals whose energies are bent on overpowering others;…‘gods’ are the very real archetype or ideological structures that determine or govern reality and its mirror, the human brain; and…‘Satan’ is the actual power that congeals around collective idolatry, injustice, or inhumanity, a power that increases or decreases according to the degree of collective refusal to choose higher values.”

In Wink’s understanding, the biblical worldview allowed its writers to comprehend the spiritual nature of human structures. The language of demons, spirits, principalities and so on helped these writers to recognize that social life has both seen and unseen elements, and that both need to be taken into account to understand the dynamics that shape our lives.

But that biblical worldview has fallen by the wayside with the development of modern consciousness and cannot simply be re-appropriated. It “is in many ways beyond being salvaged, limited as it was by the science, philosophy, and religion of its age” as Wink puts it in Unmasking the Powers.

However, the materialistic, modern worldview has itself proven inadequate in understanding and addressing complex social realities, since it cannot recognize the possibility that the spiritual Powers are real. This is crucial because, when we fail to respect the reality of the Powers we become most vulnerable to their manipulations—as, for example, when we are blind to the ways in which the myth of redemptive violence pervades ways of thinking about how best to deal with conflict and insecurity.

“A reassessment of these Powers—angels, demons, gods, elements, the devil—allows us to reclaim, name, and comprehend types of experiences that materialism renders mute and inexpressible. We have the experiences but miss their meaning. Unable to name our experiences of these intermediate powers of existence, we are simply constrained by them compulsively. They are never more powerful than when they are unconscious. Their capacities to bless us are thwarted, their capacities to possess us augmented. Unmasking these Powers can mean for us initiation into a dimension of reality ‘not known, because not looked for,’ in T.S. Eliot’s words….The goal of such unmasking is to enable people to see how they have been determined, and to free them to choose, insofar as they have genuine choice, what they will be determined by in the future.”

Therefore, we must adjust our worldview to take in the inter-related realities of internal and external power structures and make this the basis of our actions. With some success, through his writings, sermons and workshops, Wink tried to help Christians to revive the biblical worldview in a postmodern context, though his insights remain relatively unknown outside of the progressive wing of the church, at least in North America.

By challenging us to look beyond and beneath material power structures but never to ignore them, Wink's work helps us to understand how worldviews shape our perceptions of the issues that surround us, and how important it is that we revise our modern worldview if we want to move more effectively towards human wellbeing. Only an “integral worldview,” as he calls it, will enable us to remain modern people while also recognizing the interconnections of all things and the spirituality that infuses all of creation.

Along with providing necessary insights into why we are so dominated by the forces of violence, Wink’s analysis also provides an essential sense of hope and empowerment. As we break free from the illusions of the Domination System, we can be freed to recognize that not only are the Powers corruptible (or “fallen” in his language), but that they are also redeemable. So Wink’s ideas, sobering as they are, are not a counsel of despair. The Powers can—and must—be successfully resisted and transformed.

Wink argues in Naming the Powers that the language of “Principalities and Powers” in the New Testament refers to human social dynamics—institutions, belief systems, traditions and the like. These dynamics, or what he calls “manifestations of power,” always have an inner and an outer aspect. “Every Power tends to have a visible pole, an outer form—be it a church, a nation, an economy—and an invisible pole, an inner spirit or driving force that animates, legitimates, and regulates its physical manifestation in the world. Neither pole is the cause of the other. Both come into existence together and cease to exist together.”

In Wink’s view, we need such an integrated, inner-outer awareness in order to understand the world we live in and act effectively as agents for healing and transformation. “Any attempt to transform a social system without addressing both its spirituality and its outer forms is doomed to failure,” as he puts it in Engaging the Powers. What's more, in Wink's understanding all systems of power have the potential to be just or unjust, violent or nonviolent. “The Powers are good. The Powers are fallen. The Powers must be redeemed.”

“We cannot affirm governments or universities or businesses to be good unless at the same time we recognize that they are fallen,” he continues “We cannot face their malignant intractability and oppressiveness unless we remember that they are simultaneously a part of God’s good creation. And reflection on their creation and fall will appear only to legitimate these Powers and blast hope for change unless we assert at the same time that these Powers can and must be redeemed.”

This cycle of personal and institutional redemption provides a pathway to deep social change, but Wink refuses to pit the political against the personal. If either side is missing, he insists, genuine transformation won’t be possible. To illustrate what this means in concrete terms, take his analysis of contemporary North America, which focuses on the role of violence in US culture. Wink challenges what he calls the “myth of redemptive violence”—the belief that violence saves, that war brings peace, and that might makes right. His work explores how to combat this myth and further a social order that is free from domination.

A major problem in American culture has long been the devotion of an incredible amount of resources to the military-industrial complex. As a consequence, the US projects force as a solution to conflict in ways that only heighten global insecurities through a constant stream of ‘blowbacks.’ These social dynamics are fueled in part by the socialization of Americans into a mentality that insists on responding to perceived enemies with fear and violence. Wink’s analysis helps us to see how our refusal to confront the darkness within ourselves on both the personal and the societal levels blinds us to alternative approaches to enmity that can lead to a growth in self-knowledge and open up pathways to reconciliation.

His thinking about “domination systems” helps us to understand the contemporary context of large-scale violence in America and beyond, a system that entraps us all in the amazingly self-destructive dynamic of violence responding to violence, and on and on and on in this same vein. And his analysis of the role that the Principalities and Powers play in human culture helps us to make sense of why our structures are so destructive of human wellbeing.

As another example, take the crises of climate change and environmental degradation. Thus far we have not found a way to wrest control of our economic systems away from the ideologies and institutions that are driving us over the cliff of irreversible and catastrophic ecological change. Something in these systems resists change—but it is also true that our personal addictions to wasteful lifestyles and our deference to political and corporate leaders render us largely impotent.

As these examples show, the inner or spiritual Powers are not separate heavenly or ethereal realities but rather the inner aspects of material or tangible manifestations of power in relation to nature—as well, we may note, in relation to prisons, the police, racial and sexual violence, debates over gun control, militarism and the ‘War on Terror.’ As Wink writes in Naming the Powers:

“The ‘principalities and powers’ are the inner or spiritual essence, or gestalt, of an institution or system. The ‘demons’ are the psychic or spiritual power emanated by organizations or individuals or subaspects of individuals whose energies are bent on overpowering others;…‘gods’ are the very real archetype or ideological structures that determine or govern reality and its mirror, the human brain; and…‘Satan’ is the actual power that congeals around collective idolatry, injustice, or inhumanity, a power that increases or decreases according to the degree of collective refusal to choose higher values.”

In Wink’s understanding, the biblical worldview allowed its writers to comprehend the spiritual nature of human structures. The language of demons, spirits, principalities and so on helped these writers to recognize that social life has both seen and unseen elements, and that both need to be taken into account to understand the dynamics that shape our lives.

But that biblical worldview has fallen by the wayside with the development of modern consciousness and cannot simply be re-appropriated. It “is in many ways beyond being salvaged, limited as it was by the science, philosophy, and religion of its age” as Wink puts it in Unmasking the Powers.

However, the materialistic, modern worldview has itself proven inadequate in understanding and addressing complex social realities, since it cannot recognize the possibility that the spiritual Powers are real. This is crucial because, when we fail to respect the reality of the Powers we become most vulnerable to their manipulations—as, for example, when we are blind to the ways in which the myth of redemptive violence pervades ways of thinking about how best to deal with conflict and insecurity.

“A reassessment of these Powers—angels, demons, gods, elements, the devil—allows us to reclaim, name, and comprehend types of experiences that materialism renders mute and inexpressible. We have the experiences but miss their meaning. Unable to name our experiences of these intermediate powers of existence, we are simply constrained by them compulsively. They are never more powerful than when they are unconscious. Their capacities to bless us are thwarted, their capacities to possess us augmented. Unmasking these Powers can mean for us initiation into a dimension of reality ‘not known, because not looked for,’ in T.S. Eliot’s words….The goal of such unmasking is to enable people to see how they have been determined, and to free them to choose, insofar as they have genuine choice, what they will be determined by in the future.”

Therefore, we must adjust our worldview to take in the inter-related realities of internal and external power structures and make this the basis of our actions. With some success, through his writings, sermons and workshops, Wink tried to help Christians to revive the biblical worldview in a postmodern context, though his insights remain relatively unknown outside of the progressive wing of the church, at least in North America.

By challenging us to look beyond and beneath material power structures but never to ignore them, Wink's work helps us to understand how worldviews shape our perceptions of the issues that surround us, and how important it is that we revise our modern worldview if we want to move more effectively towards human wellbeing. Only an “integral worldview,” as he calls it, will enable us to remain modern people while also recognizing the interconnections of all things and the spirituality that infuses all of creation.

Along with providing necessary insights into why we are so dominated by the forces of violence, Wink’s analysis also provides an essential sense of hope and empowerment. As we break free from the illusions of the Domination System, we can be freed to recognize that not only are the Powers corruptible (or “fallen” in his language), but that they are also redeemable. So Wink’s ideas, sobering as they are, are not a counsel of despair. The Powers can—and must—be successfully resisted and transformed.

May 2, 2023: Insights:THE INFLUENCE AND IMPACT OF WALTER WINK’S ENGAGING THE POWERS

Walter Wink was an American theologian, pastor, and activist of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Ordained in the Methodist Church in 1961, he later became a Professor focussing on the New Testament and Biblical Interpretation. He taught at Union Theological Seminary and later Auburn Theological Seminary in New York. He died in 2012, leaving a profound legacy, most notably in a number of published books, leading workshops on nonviolence and contributing to the conversations surrounding sexuality and pacifism.

Wink was especially known for his work on power structures, culminating in a trilogy of works – Naming the Powers: The Language of Power in the New Testament, Unmasking the Powers: The Invisible Forces That Determine Human Existence, and Engaging the Powers: Discernment and Resistance in a World of Domination. In these three books, Wink challenged the notion of conceptualising the Powers of the New Testament as an order of angelic and demonic beings in heaven or as simply institutions and systems. Rather he proposed that Paul’s framework of Powers as presented in Ephesians 6:12 was concerned with structural, social, political and state Powers.

Walter Wink was an American theologian, pastor, and activist of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Ordained in the Methodist Church in 1961, he later became a Professor focussing on the New Testament and Biblical Interpretation. He taught at Union Theological Seminary and later Auburn Theological Seminary in New York. He died in 2012, leaving a profound legacy, most notably in a number of published books, leading workshops on nonviolence and contributing to the conversations surrounding sexuality and pacifism.

Wink was especially known for his work on power structures, culminating in a trilogy of works – Naming the Powers: The Language of Power in the New Testament, Unmasking the Powers: The Invisible Forces That Determine Human Existence, and Engaging the Powers: Discernment and Resistance in a World of Domination. In these three books, Wink challenged the notion of conceptualising the Powers of the New Testament as an order of angelic and demonic beings in heaven or as simply institutions and systems. Rather he proposed that Paul’s framework of Powers as presented in Ephesians 6:12 was concerned with structural, social, political and state Powers.

Walter Wink Files

Walter Wink Files

"The church says to the lion and the lamb, "Here, let me negotiate a truce," to which the lion replies, "Fine, after I finish my lunch."

"Most Christians desire nonviolence, yes; but they are not talking about a nonviolent struggle for justice. They mean simply the absence of conflict."

-Walter Wink; Jesus and Nonviolence: A Third Way (2003), p. 4

"Most Christians desire nonviolence, yes; but they are not talking about a nonviolent struggle for justice. They mean simply the absence of conflict."

-Walter Wink; Jesus and Nonviolence: A Third Way (2003), p. 4

Walter Wink Files

Walter Wink Files

In the biblical view they are both visible and invisible, earthly and heavenly, spiritual and institutional. The Powers possess an outer, physical manifestation (buildings, portfolios, personnel, trucks, fax machines) and an inner spirituality, or corporate culture, or collective personality. The Powers are the simultaneity of an outer, visible structure and an inner, spiritual reality. The Powers, properly speaking, are not just the spirituality of institutions, but their outer manifestations as well…what people in the world of the Bible experienced and called “Principalities and Powers” was in fact real. They were discerning the actual spirituality at the center of the political, economic, and cultural institutions of their day. The spiritual aspect of the Powers is not simply a “personification” of institutional qualities that would exist whether they were personified or not. On the contrary, the spirituality of an institution exists as a real aspect of the institution even when it is not perceived as such. Institutions have an actual spiritual ethos…

--Walter Wink; Engaging the Powers: Discernment and Resistance in a World of Domination (1992)

--Walter Wink; Engaging the Powers: Discernment and Resistance in a World of Domination (1992)

Walter Wink Files

Walter Wink Files

“for God's sake, let's be done with the hypocrisy of claiming "I am a biblical literalist" when everyone is a selective literalist, especially those who swear by the antihomosexual laws in the Book of Leviticus and then feast on barbecued ribs and delight in Monday-night football, for it is toevali, an abomination, not only to eat pork but merely to touch the skin of a dead pig.”

― Walter Wink, Homosexuality and Christian Faith: Questions of Conscience for the Churches

― Walter Wink, Homosexuality and Christian Faith: Questions of Conscience for the Churches

Walter Wink Files

Walter Wink Files

“The issue is not, "What must I do in order to secure my salvation?" but rather, "What does God require of me in response to the needs of others?" It is not, "How can I be virtuous?" but "How can I participate in the struggle of the oppressed for a more just world?" Otherwise our nonviolence is premised on self-justifying attempts to establish our own purity in the eyes of God, others, and ourselves, and that is nothing less than a satanic temptation to die with clean hands and a dirty heart.”

― Walter Wink, Jesus and Nonviolence: A Third Way

― Walter Wink, Jesus and Nonviolence: A Third Way

Walter Wink Files

Walter Wink Files

“The command to love our enemies reminds us that our first task towards oppressors is pastoral: to help them recover their humanity. Quite possibly the struggle, and the oppression that gave it rise, have dehumanised the oppressed as well, causing them to demonise their enemies. It is not enough to become politically free; we must also become human. Nonviolence presents a change for all parties to rise above their present condition and become more of what God created them to be.”

― Walter Wink, The Powers That Be: Theology for a New Millennium

― Walter Wink, The Powers That Be: Theology for a New Millennium

Walter Wink Files

Walter Wink Files

It cannot be stressed too much: love of enemies has, for our time, become the litmus test of authentic Christian faith. Commitment to justice, liberation or the overthrow of opposition is not enough, for all too often the means used have brought in their wake new injustices and oppressions. Love of enemies is the recognition that the enemy, too, is a child of God. The enemy too believes he or she is in the right, and fears us because we represent a threat against his or her values, lifestyle, or affluence. When we demonize our enemies, calling them names and identifying them with absolute evil, we deny that they have that of God within them that makes transformation possible. Instead, we play God. We write them out of the Book of Life. We conclude that our enemy has drifted beyond the redemptive hand of God. I submit that the ultimate religious question today is no longer the Reformation's "How can I find a gracious God?" It is instead, "How can I find God in my enemy?" What guilt was for Luther, the enemy has become for us: the goad that can drive us to God. What has formerly been a purely private affair — justification by faith through grace — has now, in our age, grown to embrace the world. As John Stoner comments, we can no more save ourselves from our enemies than we can save ourselves from sin, but God's amazing grace offers to save us from both. There is, in fact, no other way to God for our time but through the enemy, for loving the enemy has become the key both to human survival in the age of terror and to personal transformation. Either we find the God who causes the sun to rise on the evil and the good, or we may have no more sunrises. — Walter Wink, Jesus and Nonviolence

Walter Wink Files

Walter Wink Files

“There is no one, and surely no entire people, in whom the image of God has been utterly extinguished. Faith in God means believing that anyone can be transformed, regardless of the past. To write off whole groups of people as intrinsically racist and violent is to accept the very same premise that upholds racist and oppressive regimes.”

— Walter Wink

Walter Wink Files

Walter Wink Files

History Belongs to the Intercessors by Walter Wink

Intercessory prayer is spiritual defiance of what is in the way of what God has promised. Intercession visualizes an alternative future to the one apparently fated by the momentum of current forces. Prayer infuses the air of a time yet to be into the suffocating atmosphere of the present. History belongs to the intercessors who believe the future into being. Even a small number of people, firmly committed to the new inevitability on which they have fixed their imaginations, can decisively affect the shape the future takes. These shapers of the future are the intercessors, who call out of the future the longed-for new present. In the New Testament, the name and texture and aura of that future is God's domination-free order, the reign of God. No doubt our intercessions sometimes change us as we open ourselves to new possibilities we had not guessed. No doubt our prayers to God reflect back upon us as a divine command to become the answer to our prayer. But if we are to take the biblical understanding seriously, intercession is more than that. It changes the world and it changes what is possible. It creates an island of relative freedom in a world gripped by unholy necessity. A new force appears that hitherto was only potential. The entire configuration changes as the result of the change of a single part. A space opens in the praying person, permitting God to act without violating human freedom. All of Jesus' teachings on prayer feature imperatives. (Ex. Lk 11:9 "Ask . . .search . . . knock.") In prayer we are ordering God to bring the Kingdom near. It will not do to implore. We have been commanded to command. We are required by God to haggle with God for the sake of the sick, the obsessed, the weak, and to conform our lives to our intercessions. This is a God who invents history in interaction with those "who hunger and thirst to see right prevail" (Mat. 5:6, REB). How different this is from the static god of Greek philosophy that all these years has lulled so many into adoration without intercession! When we pray we are not sending a letter to a celestial White House, where it is sorted among piles of others. We are engaged, rather, in an act of co-creation, in which one little sector of the universe rises up and becomes translucent, incandescent, a vibratory centre of power that radiates the power of the universe. History belongs to the intercessors, who believe the future into being. If this is so, then intercession, far from being an escape from action, is a means of focusing for action and of creating action. By means of our intercessions we veritably cast fire upon the earth and trumpet the future into being.

Intercessory prayer is spiritual defiance of what is in the way of what God has promised. Intercession visualizes an alternative future to the one apparently fated by the momentum of current forces. Prayer infuses the air of a time yet to be into the suffocating atmosphere of the present. History belongs to the intercessors who believe the future into being. Even a small number of people, firmly committed to the new inevitability on which they have fixed their imaginations, can decisively affect the shape the future takes. These shapers of the future are the intercessors, who call out of the future the longed-for new present. In the New Testament, the name and texture and aura of that future is God's domination-free order, the reign of God. No doubt our intercessions sometimes change us as we open ourselves to new possibilities we had not guessed. No doubt our prayers to God reflect back upon us as a divine command to become the answer to our prayer. But if we are to take the biblical understanding seriously, intercession is more than that. It changes the world and it changes what is possible. It creates an island of relative freedom in a world gripped by unholy necessity. A new force appears that hitherto was only potential. The entire configuration changes as the result of the change of a single part. A space opens in the praying person, permitting God to act without violating human freedom. All of Jesus' teachings on prayer feature imperatives. (Ex. Lk 11:9 "Ask . . .search . . . knock.") In prayer we are ordering God to bring the Kingdom near. It will not do to implore. We have been commanded to command. We are required by God to haggle with God for the sake of the sick, the obsessed, the weak, and to conform our lives to our intercessions. This is a God who invents history in interaction with those "who hunger and thirst to see right prevail" (Mat. 5:6, REB). How different this is from the static god of Greek philosophy that all these years has lulled so many into adoration without intercession! When we pray we are not sending a letter to a celestial White House, where it is sorted among piles of others. We are engaged, rather, in an act of co-creation, in which one little sector of the universe rises up and becomes translucent, incandescent, a vibratory centre of power that radiates the power of the universe. History belongs to the intercessors, who believe the future into being. If this is so, then intercession, far from being an escape from action, is a means of focusing for action and of creating action. By means of our intercessions we veritably cast fire upon the earth and trumpet the future into being.

Oct 14, 2022: CBC Radio: Turn the Other Cheek: the radical case for nonviolent resistance

The late Walter Wink was one of the most influential voices in Christian theology of nonviolence; he unpacked the language of 'turn the other cheek' in Matthew's Gospel and taught that Jesus was pointing to a third way: not fight, not flight, but an active, nonviolent challenge to the oppressor.

Derek Suderman, an associate professor at Conrad Grebel University College in Waterloo, Ontario, says Wink's interpretation of 'turn the other cheek' was influenced by his time in South Africa during the apartheid era.

The late Walter Wink was one of the most influential voices in Christian theology of nonviolence; he unpacked the language of 'turn the other cheek' in Matthew's Gospel and taught that Jesus was pointing to a third way: not fight, not flight, but an active, nonviolent challenge to the oppressor.

Derek Suderman, an associate professor at Conrad Grebel University College in Waterloo, Ontario, says Wink's interpretation of 'turn the other cheek' was influenced by his time in South Africa during the apartheid era.

May 29, 2012: NCR: Walter Wink, our best teacher of Christian nonviolence

"Whoever obeys and teaches these commandments will be called the greatest in the kingdom of heaven."(Mt. 5:19) That's what Jesus announced in the Sermon on the Mount, right after the beatitudes and just before the six antitheses, which instruct us to resist evil nonviolently and to love our enemies. In light of that verse, Walter Wink must be considered one of the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. I can think of no higher praise.

"Whoever obeys and teaches these commandments will be called the greatest in the kingdom of heaven."(Mt. 5:19) That's what Jesus announced in the Sermon on the Mount, right after the beatitudes and just before the six antitheses, which instruct us to resist evil nonviolently and to love our enemies. In light of that verse, Walter Wink must be considered one of the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. I can think of no higher praise.

Walter Wink argues in Naming the Powers that the language of “Principalities and Powers” in the New Testament refers to human social dynamics—institutions, belief systems, traditions and the like. These dynamics, or what he calls “manifestations of power,” always have an inner and an outer aspect. “Every Power tends to have a visible pole, an outer form—be it a church, a nation, an economy—and an invisible pole, an inner spirit or driving force that animates, legitimates, and regulates its physical manifestation in the world. Neither pole is the cause of the other. Both come into existence together and cease to exist together.” -Open Democracy

Jan 1992: Engaging the Powers: Discernment and Resistance in a World of Domination is published by Fortress Press. Wink explores the problem of evil today and how it relates to the New Testament concept of Principalities and Powers. He asks the question "How can we oppose evil without creating new evils and being made evil ourselves?" Winner of the Pax Christi Award, the Academy of Parish Clergy Book of the Year, and the Midwest Book Achievement Award for Best Religious Book.

January 5, 1984: Naming the Powers: The Language of Power in the New Testament is published by Augsburg Fortress Publishers.

From the introduction: "The reader of this work will search in vain for a definition of power. It is one of those words that everyone understands perfectly well until asked to define it. Our use of the term 'power' is laden with assumptions drawn from the contemporary materialistic worldview. Whereas the ancients always understood power as the confluence of both spiritual and material factors, we tend to see it as primarily material. We do not think in terms of spirits, ghosts, demons, or gods as the effective agents of powerful effects in the world. Thus a gulf has been fixed between us and the biblical writers. We use the same words but project them into a wholly different world of meanings. What they meant by power and what we mean are incommensurate. If our goal is to understand the New Testament's conception of the Powers, we cannot do so simply by applying our own modern sociological categories of power. We must instead attend carefully and try to grasp what the people of that time might have meant by power, within the linguistic field of their own worldview and mythic systems. "I will argue that the "principalities and powers" are the inner and outer aspects of any given manifestation of power. As the inner aspect they are the spirituality of institutions, the "within" of corporate structures and systems, the inner essence of outer organizations of power. As the outer aspect they are political systems, appointed officials, the "chair" of an organization, laws in short, all the tangible manifestations which power takes. This hypothesis, it seems to me, makes sense of the fluid way the New Testament writers and their contemporaries spoke of the Powers, now as if they were these centurions or that priestly hierarchy, and then, with no warning, as if they were some kind of spiritual entities in the heavenly places."

From the introduction: "The reader of this work will search in vain for a definition of power. It is one of those words that everyone understands perfectly well until asked to define it. Our use of the term 'power' is laden with assumptions drawn from the contemporary materialistic worldview. Whereas the ancients always understood power as the confluence of both spiritual and material factors, we tend to see it as primarily material. We do not think in terms of spirits, ghosts, demons, or gods as the effective agents of powerful effects in the world. Thus a gulf has been fixed between us and the biblical writers. We use the same words but project them into a wholly different world of meanings. What they meant by power and what we mean are incommensurate. If our goal is to understand the New Testament's conception of the Powers, we cannot do so simply by applying our own modern sociological categories of power. We must instead attend carefully and try to grasp what the people of that time might have meant by power, within the linguistic field of their own worldview and mythic systems. "I will argue that the "principalities and powers" are the inner and outer aspects of any given manifestation of power. As the inner aspect they are the spirituality of institutions, the "within" of corporate structures and systems, the inner essence of outer organizations of power. As the outer aspect they are political systems, appointed officials, the "chair" of an organization, laws in short, all the tangible manifestations which power takes. This hypothesis, it seems to me, makes sense of the fluid way the New Testament writers and their contemporaries spoke of the Powers, now as if they were these centurions or that priestly hierarchy, and then, with no warning, as if they were some kind of spiritual entities in the heavenly places."