T - Past-Witnesses-Files

- Theodore G Tappert - Hudson Taylor - Tertullian - H. Chungthang Thiek - Howard Thurman - Desmond Tutu -

theodore g tappert

Theodore G. Tappert (May 5, 1904–December 25, 1973) was a distinguished church historian and author. He was Schieren Professor of the History of Christianity at Lutheran Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. Tappert was also archivist of the Southeastern Pennsylvania Synod and a consultant to the Lutheran Church in American's Board of Publication.

Theodore G Tappert

Theodore G Tappert

God has promised us assurance that everything is forgiven and pardoned, yet on the condition that we also forgive our neighbor....If you do not forgive, do not think that God forgives you. But if you forgive, you have the comfort and assurance that you are forgiven in heaven. Not on account of your forgiving, for God does it altogether freely....But he has set up this condition for our strengthening and assurance as a sign along with the promise which is in agreement with this petition, Luke 6:37, Forgive, and you will be forgiven. Therefore Christ repeats it immediately after the Lord’s Prayer in Matt. 6:14, saying, If you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father also will forgive you, etc. --The Book of Concord: The Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church, ed. Theodore G. Tappert (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1959)

hudson Taylor

Hudson Taylor Files

Hudson Taylor Files

I felt the ingratitude, the danger, the sin of not living nearer to God. I prayed, agonised, fasted, strove, made resolutions, read the Word more diligently, sought more time for retirement and meditation—but all was without effect. Every day, almost every hour, the consciousness of sin oppressed me. I knew that if I could only abide in Christ all would be well, but I could not. I began the day with prayer, determined not to take my eye from Him for a moment; but pressure of duties, sometimes very trying, constant interruptions apt to be so wearing, often caused me to forget Him. Then one's nerves get so fretted in this climate that temptations to irritability, hard thoughts, and sometimes unkind words are all the more difficult to control. Each day brought its register of sin and failure, of lack of power. To will was indeed present with me, but how to perform I found not.

Then came the question, "Is there no rescue? Must it be thus to the end—constant conflict and, instead of victory, too often defeat?" How, too, could I preach with sincerity that to those who receive Jesus, "to them gave He power to become the sons of God" (i.e. God-like) when it was not so in my own experience? Instead of growing stronger, I seemed to be getting weaker and to have less power against sin; and no wonder, for faith and even hope were getting very low. I hated myself; I hated my sin; and yet I gained no strength against it. I felt I was a child of God: His Spirit in my heart would cry, in spite of all, "Abba, Father": but to rise to my privileges as a child, I was utterly powerless. I thought that holiness, practical holiness, was to be gradually attained by a diligent use of the means of grace. I felt that there was nothing I so much desired in this world, nothing I so much needed. But so far from in any measure attaining it, the more I pursued and strove after it, the more it eluded my grasp; till hope itself almost died out, and I began to think that, perhaps to make heaven the sweeter, God would not give it down here. I do not think I was striving to attain it in my own strength. I knew I was powerless. I told the Lord so, and asked Him to give me help and strength; and sometimes I almost believed He would keep and uphold me. But on looking back in the evening, alas! there was but sin and failure to confess and mourn before God.

I would not give you the impression that this was the daily experience of all those long, weary months. It was a too frequent state of soul; that toward which I was tending, and which almost ended in despair. And yet never did Christ seem more precious—a Saviour who could and would save such a sinner! ... And sometimes there were seasons not only of peace but of joy in the Lord. But they were transitory, and at best there was a sad lack of power. Oh, how good the Lord was in bringing this conflict to an end!

All the time I felt assured that there was in Christ all I needed, but the practical question was how to get it out. He was rich, truly, but I was poor; He strong, but I weak. I knew full well that there was in the root, the stem, abundant fatness; but how to get it into my puny little branch was the question. As gradually the light was dawning on me, I saw that faith was the only prerequisite, was the hand to lay hold on His fulness and make it my own. But I had not this faith. I strove for it, but it would not come; tried to exercise it, but in vain. Seeing more and more the wondrous supply of grace laid up in Jesus, the fulness of our precious Saviour—my helplessness and guilt seemed to increase. Sins committed appeared but as trifles compared with the sin of unbelief which was their cause, which could not or would not take God at His word, but rather made Him a liar! Unbelief was, I felt, the damning sin of the world—yet I indulged in it. I prayed for faith, but it came not. What was I to do?

When my agony of soul was at its height, a sentence in a letter from dear McCarthy [John McCarthy, in Hangchow] was used to remove the scales from my eyes, and the Spirit of God revealed the truth of our oneness with Jesus as I had never known it before. McCarthy, who had been much exercised by the same sense of failure, but saw the light before I did, wrote (I quote from memory):

"But how to get faith strengthened? Not by striving after faith, but by resting on the Faithful One."

As I read I saw it all! "If we believe not, He abideth faithful." I looked to Jesus and saw (and when I saw, oh, how joy flowed!) that He had said, "I will never leave you." "Ah, there is rest!" I thought. "I have striven in vain to rest in Him. I'll strive no more. For has He not promised to abide with me—never to leave me, never to fail me?" And, dearie, He never will!

But this was not all He showed me, nor one half. As I thought of the Vine and the branches, what light the blessed Spirit poured direct into my soul! How great seemed my mistake in having wished to get the sap, the fulness out of Him. I saw not only that Jesus would never leave me, but that I was a member of His body, of His flesh and of His bones. The vine now I see, is not the root merely, but all—root, stem, branches, twigs, leaves, flowers, fruit: and Jesus is not only that: He is soil and sunshine, air and showers, and ten thousand times more than we have ever dreamed, wished for, or needed. Oh, the joy of seeing this truth! I do pray that the eyes of your understanding may be enlightened, that you may know and enjoy the riches freely given us in Christ.

--From a letter by J. Hudson Taylor, Chinkiang, October 17th, 1869, to his sister Amelia (Mrs. Broomhall), in England

Then came the question, "Is there no rescue? Must it be thus to the end—constant conflict and, instead of victory, too often defeat?" How, too, could I preach with sincerity that to those who receive Jesus, "to them gave He power to become the sons of God" (i.e. God-like) when it was not so in my own experience? Instead of growing stronger, I seemed to be getting weaker and to have less power against sin; and no wonder, for faith and even hope were getting very low. I hated myself; I hated my sin; and yet I gained no strength against it. I felt I was a child of God: His Spirit in my heart would cry, in spite of all, "Abba, Father": but to rise to my privileges as a child, I was utterly powerless. I thought that holiness, practical holiness, was to be gradually attained by a diligent use of the means of grace. I felt that there was nothing I so much desired in this world, nothing I so much needed. But so far from in any measure attaining it, the more I pursued and strove after it, the more it eluded my grasp; till hope itself almost died out, and I began to think that, perhaps to make heaven the sweeter, God would not give it down here. I do not think I was striving to attain it in my own strength. I knew I was powerless. I told the Lord so, and asked Him to give me help and strength; and sometimes I almost believed He would keep and uphold me. But on looking back in the evening, alas! there was but sin and failure to confess and mourn before God.

I would not give you the impression that this was the daily experience of all those long, weary months. It was a too frequent state of soul; that toward which I was tending, and which almost ended in despair. And yet never did Christ seem more precious—a Saviour who could and would save such a sinner! ... And sometimes there were seasons not only of peace but of joy in the Lord. But they were transitory, and at best there was a sad lack of power. Oh, how good the Lord was in bringing this conflict to an end!

All the time I felt assured that there was in Christ all I needed, but the practical question was how to get it out. He was rich, truly, but I was poor; He strong, but I weak. I knew full well that there was in the root, the stem, abundant fatness; but how to get it into my puny little branch was the question. As gradually the light was dawning on me, I saw that faith was the only prerequisite, was the hand to lay hold on His fulness and make it my own. But I had not this faith. I strove for it, but it would not come; tried to exercise it, but in vain. Seeing more and more the wondrous supply of grace laid up in Jesus, the fulness of our precious Saviour—my helplessness and guilt seemed to increase. Sins committed appeared but as trifles compared with the sin of unbelief which was their cause, which could not or would not take God at His word, but rather made Him a liar! Unbelief was, I felt, the damning sin of the world—yet I indulged in it. I prayed for faith, but it came not. What was I to do?

When my agony of soul was at its height, a sentence in a letter from dear McCarthy [John McCarthy, in Hangchow] was used to remove the scales from my eyes, and the Spirit of God revealed the truth of our oneness with Jesus as I had never known it before. McCarthy, who had been much exercised by the same sense of failure, but saw the light before I did, wrote (I quote from memory):

"But how to get faith strengthened? Not by striving after faith, but by resting on the Faithful One."

As I read I saw it all! "If we believe not, He abideth faithful." I looked to Jesus and saw (and when I saw, oh, how joy flowed!) that He had said, "I will never leave you." "Ah, there is rest!" I thought. "I have striven in vain to rest in Him. I'll strive no more. For has He not promised to abide with me—never to leave me, never to fail me?" And, dearie, He never will!

But this was not all He showed me, nor one half. As I thought of the Vine and the branches, what light the blessed Spirit poured direct into my soul! How great seemed my mistake in having wished to get the sap, the fulness out of Him. I saw not only that Jesus would never leave me, but that I was a member of His body, of His flesh and of His bones. The vine now I see, is not the root merely, but all—root, stem, branches, twigs, leaves, flowers, fruit: and Jesus is not only that: He is soil and sunshine, air and showers, and ten thousand times more than we have ever dreamed, wished for, or needed. Oh, the joy of seeing this truth! I do pray that the eyes of your understanding may be enlightened, that you may know and enjoy the riches freely given us in Christ.

--From a letter by J. Hudson Taylor, Chinkiang, October 17th, 1869, to his sister Amelia (Mrs. Broomhall), in England

--tertullian------------------------------

June 16, 2023: Desiring God: The Seeds None Could Afford

Nevertheless, there were certainly many people who went to their deaths because they refused to renounce their devotion to Christ. Why was this? The church father Tertullian (c. 155–c. 220) offers a fascinating window into early Christian martyrdom — and how God used it to build his church.

Nevertheless, there were certainly many people who went to their deaths because they refused to renounce their devotion to Christ. Why was this? The church father Tertullian (c. 155–c. 220) offers a fascinating window into early Christian martyrdom — and how God used it to build his church.

--H Chungthang thiek------------------------------

Manipur Evangelical prayer movement leader dies: 'A void that will be deeply felt'

The Rev. H. Chungthang Thiek, a prominent evangelist and former secretary of the Evangelical Fellowship of India's northeast region, has died, leaving a profound legacy in northeast India's spiritual and social spheres. He was 75. His 27-year tenure at EFI, from 1988 to 2015, was marked by significant contributions to the organization and the broader Church community, said the EFI, a national alliance of Evangelical Christians, in a Jan. 4 statement. He is credited with launching the "Prayer Mountain" movement near Churachandpur.

(Anugrah Kumar/Christian Post)

READ MORE>>>>>

The Rev. H. Chungthang Thiek, a prominent evangelist and former secretary of the Evangelical Fellowship of India's northeast region, has died, leaving a profound legacy in northeast India's spiritual and social spheres. He was 75. His 27-year tenure at EFI, from 1988 to 2015, was marked by significant contributions to the organization and the broader Church community, said the EFI, a national alliance of Evangelical Christians, in a Jan. 4 statement. He is credited with launching the "Prayer Mountain" movement near Churachandpur.

(Anugrah Kumar/Christian Post)

READ MORE>>>>>

--howard thurman------------------------------

|

(November 18, 1899 – April 10, 1981)

|

Howard Washington Thurman (November 18, 1899 – April 10, 1981) was an American author, philosopher, theologian, mystic, educator, and civil rights leader. As a prominent religious figure, he played a leading role in many social justice movements and organizations of the twentieth century. Thurman's theology of radical nonviolence influenced and shaped a generation of civil rights activists, and he was a key mentor to leaders within the civil rights movement, including Martin Luther King Jr. In 1944 Thurman left his position as dean at Howard University to co-found the first fully integrated, multi-cultural church in the U.S. in San Francisco, CA. The Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples was a revolutionary idea. Founded on the ideal of diverse community with a focus on a common faith in God, Thurman brought people of every ethnic background together to worship and work for peace. "Do not be silent; there is no limit to the power that may be released through you."

May 23, 2023: Boston University: Howard Thurman Center Taps Veteran Staffer as New Leader

A nationwide search for the new leader of BU’s “campus living room” found the ideal person was already in the room. Nick Bates, the Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground’s (HTC) interim director, has been named its new director, effective immediately.

A nationwide search for the new leader of BU’s “campus living room” found the ideal person was already in the room. Nick Bates, the Howard Thurman Center for Common Ground’s (HTC) interim director, has been named its new director, effective immediately.

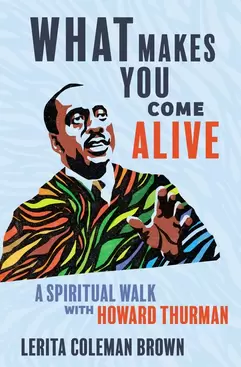

What Makes You Come Alive

What Makes You Come Alive

April 23, 2023: The Living Church: Learning from Martin Luther King’s Mentor

Those familiar with the late Howard Thurman know that he was considered the spiritual director of the civil rights movement and that Martin Luther King Jr. carried Jesus and the Disinherited in his coat pocket while marching for social change. “Part of Howard Thurman’s response to God was to provide the spiritual and philosophical underpinnings for the work that calls people to action,” Lerita Coleman Brown writes.

Coleman Brown relates how racism was a very real presence throughout Thurman’s life, but through the spiritual nurturing of his mother and grandmother, a former slave who could not read, he learned to know the Creator of the universe by reading Scripture and by being in nature. As a young boy he found that silence and solitude were important spiritual disciplines that enabled him to “center down” and commune with the Transcendent. Coleman Brown relates how her introduction to this important figure legitimized her questions about the lack of Black and Brown voices in the contemplative stream of Christianity.

Thurman observed that Jesus was a contemplative, as he often prayed alone in the early morning or late in the day after the crowds had gone away: “This was the time for the long breath, when all the fragments left by the commonplace, when all the hurts and the big aches could be absorbed, and the mind could be freed of the immediate demand, when voices that had been quieted by the long day’s work could once more be heard, when there could be the deep sharing of the innermost secrets and the laying bare of the heart and mind.” Thurman’s words are seamlessly woven into the text throughout the book.

Each chapter discusses an aspect of Thurman’s core beliefs, and relates them to Coleman Brown’s experiences of living as a Black woman in the United States. Coleman Brown relates the importance of Thurman’s beliefs to everyday spiritual seekers. She teaches that deep connection with the living God is not just for monks, but for everyone. Thurman’s belief that everyone is a holy child of God, spiritually and psychologically, anchors us in all areas of life. She expands on this theme: “Inner Authority does not emerge from us, but from Spirit within,” and “beneath all our ego desires — for importance, fortune, power, and possessions — is a hunger for our Creator.”

Each chapter ends with reflection questions and spiritual steps, which would be very useful in an individual or group study. This book taught me more about Thurman, one of the most important and yet less-known leaders of the 20th-century American church. But more than that, it made me think and feel deeply about the different aspects of Thurman’s doctrine, and how being a holy child of God plays out in my life. I hope many read this book and have the same experience. --Living Church

Those familiar with the late Howard Thurman know that he was considered the spiritual director of the civil rights movement and that Martin Luther King Jr. carried Jesus and the Disinherited in his coat pocket while marching for social change. “Part of Howard Thurman’s response to God was to provide the spiritual and philosophical underpinnings for the work that calls people to action,” Lerita Coleman Brown writes.

Coleman Brown relates how racism was a very real presence throughout Thurman’s life, but through the spiritual nurturing of his mother and grandmother, a former slave who could not read, he learned to know the Creator of the universe by reading Scripture and by being in nature. As a young boy he found that silence and solitude were important spiritual disciplines that enabled him to “center down” and commune with the Transcendent. Coleman Brown relates how her introduction to this important figure legitimized her questions about the lack of Black and Brown voices in the contemplative stream of Christianity.

Thurman observed that Jesus was a contemplative, as he often prayed alone in the early morning or late in the day after the crowds had gone away: “This was the time for the long breath, when all the fragments left by the commonplace, when all the hurts and the big aches could be absorbed, and the mind could be freed of the immediate demand, when voices that had been quieted by the long day’s work could once more be heard, when there could be the deep sharing of the innermost secrets and the laying bare of the heart and mind.” Thurman’s words are seamlessly woven into the text throughout the book.

Each chapter discusses an aspect of Thurman’s core beliefs, and relates them to Coleman Brown’s experiences of living as a Black woman in the United States. Coleman Brown relates the importance of Thurman’s beliefs to everyday spiritual seekers. She teaches that deep connection with the living God is not just for monks, but for everyone. Thurman’s belief that everyone is a holy child of God, spiritually and psychologically, anchors us in all areas of life. She expands on this theme: “Inner Authority does not emerge from us, but from Spirit within,” and “beneath all our ego desires — for importance, fortune, power, and possessions — is a hunger for our Creator.”

Each chapter ends with reflection questions and spiritual steps, which would be very useful in an individual or group study. This book taught me more about Thurman, one of the most important and yet less-known leaders of the 20th-century American church. But more than that, it made me think and feel deeply about the different aspects of Thurman’s doctrine, and how being a holy child of God plays out in my life. I hope many read this book and have the same experience. --Living Church

Jan 11, 2018: Urban Faith: MEET THE THEOLOGIAN WHO HELPED MLK SEE THE VALUE OF NONVIOLENCE

For African-Americans who grew up with the legacy of segregation, disfranchisement, lynching, and violence, retreat from social struggle was unthinkable. Martin Luther King Jr., however, learned from some important mentors how to integrate spiritual growth and social transformation.

As a historian, who has studied how figures in American history struggled with similar questions, I believe one major influence on King’s thought was the African-American minister, theologian, and mystic Howard Thurman.

For African-Americans who grew up with the legacy of segregation, disfranchisement, lynching, and violence, retreat from social struggle was unthinkable. Martin Luther King Jr., however, learned from some important mentors how to integrate spiritual growth and social transformation.

As a historian, who has studied how figures in American history struggled with similar questions, I believe one major influence on King’s thought was the African-American minister, theologian, and mystic Howard Thurman.

desmond tutu

Dec 30, 2021: Religion News: Observers, detractors and preachers of religion who died in 2021

Retired Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The man who became synonymous with South Africa’s nonviolent struggle against apartheid earned the Nobel Peace Prize for railing against the racially oppressive regime that stifled his country. Tutu died Sunday (Dec. 26) at 90.

The spiritual leader of millions of Black and white South Africans headed his country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission and withstood critics who rejected his determination to protest racial segregation and to seek nonviolent solutions. His honors included the Presidential Medal of Freedom from then-President Barack Obama in 2009 and the Templeton Prize, a top award in the field of religion and spirituality, in 2013.

Later in life, the first Black Anglican bishop of Johannesburg continued to preach about the need for forgiveness and reconciliation, extending his message about justice to advocate for poor people, support Palestinians, and speak out for gay rights.

“All, all are God’s children and none, none is ever to be dismissed as rubbish,” he once told a “God and Us” class he taught as a visiting professor at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. “And that’s why you have to be so passionate in your opposition to injustice of any kind.”

Retired Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The man who became synonymous with South Africa’s nonviolent struggle against apartheid earned the Nobel Peace Prize for railing against the racially oppressive regime that stifled his country. Tutu died Sunday (Dec. 26) at 90.

The spiritual leader of millions of Black and white South Africans headed his country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission and withstood critics who rejected his determination to protest racial segregation and to seek nonviolent solutions. His honors included the Presidential Medal of Freedom from then-President Barack Obama in 2009 and the Templeton Prize, a top award in the field of religion and spirituality, in 2013.

Later in life, the first Black Anglican bishop of Johannesburg continued to preach about the need for forgiveness and reconciliation, extending his message about justice to advocate for poor people, support Palestinians, and speak out for gay rights.

“All, all are God’s children and none, none is ever to be dismissed as rubbish,” he once told a “God and Us” class he taught as a visiting professor at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. “And that’s why you have to be so passionate in your opposition to injustice of any kind.”