- Tom Ashbrook - Annika Brockschmidt - Tucker Carlson - James Carville - Sean Hannity - Laura Ingraham - Dan Kennedy - Kathy Jean Lopez - Amanda Marcotte - Matt Mcmanus - Elon Musk - Candace Owens - Jeanine Pirro - Jen Psaki - Ben Shapiro -

tom ashbrook

Thomas E. Ashbrook is an American journalist and radio broadcaster. He was formerly the host of the nationally syndicated, public radio call-in program On Point, from which he was dismissed after an investigation concluded he had created a hostile work environment. Prior to working with On Point, he was a foreign correspondent in Asia, and foreign editor of The Boston Globe. He currently hosts a podcast, Tom Ashbrook—Conversations .

Dan Kennedy

Dan Kennedy

I listened to the podcast of “On Point” host Tom Ashbrook’s recent interview with the poet and author Jay Parini. The subject was Parini’s new book, “Jesus: The Human Face of God” (Icons).

I was fascinated. Here was someone who described himself as a believer — an Episcopalian, the denomination of my youth, no less — who spoke of Jesus and Christianity in terms of myth and metaphor rather than as some sort of rigid, literal reality. I wanted to see how he brought the seeming contradictions of belief and mythology together.

Unfortunately, the book itself does not quite live up to the promise of Parini’s conversation with Ashbrook, mainly because he tries to have it too many ways — starting with what it means to be a believer. “In its Greek and Latin roots,” he writes, “the word ‘believe’ simply means ‘giving one’s deepest self to’ something.” And he quotes St. Anselm: “For I do not seek to understand so that I may believe, but I believe so that I may understand.” To my way of thinking, that is putting the metaphorical cart before the metaphorical horse.

My principal unease with Parini, though, is that he writes about “remythologizing” Jesus without quite doing so. On the one hand, he suggests that the miracles Jesus performed and his resurrection are not meant to be taken literally. On the other, he does not rule out the possibility that they actually did happen. Parini doesn’t seem to think it matters all that much whether Jesus came back from the dead metaphorically or materially. Yet to me that’s the most important question.

I say that in full awareness of my own intellectual limitations. Like most people who were educated in a Western context, my thinking tends to be binary. My attitude toward religion is that it’s either literally true or it isn’t; and since it almost certainly isn’t, then it’s something I needn’t trouble myself with. Mind you, I have no patience for Christopher Hitchens-style atheism, and I’m intrigued enough by the whole notion of spirituality to attend a Unitarian Universalist church. But belief to me is a state of mind, based on provable facts, and not something I would give my “deepest self” to in the absence of such facts.

Still, there is much to recommend in Parini’s short biography. Parini is a warm and humane guide to the life of Jesus and the early roots of Christianity. He is especially valuable in explaining Jesus “the religious genius” who synthesized Jewish, Greek and Eastern ideas, especially in the Sermon on the Mount. Parini’s learned exploration of Jesus’ moral and spiritual teachings transcends the reality-versus-metaphor divide.

If you’re looking for answers, then “Jesus” is not for you. There are none, and Parini doesn’t pretend otherwise. But if you’re interested in a different way of thinking about Christianity, then Parini’s brief guide is a good place to start.

--Dan Kennedy; Media Nation; Myth, reality and Jay Parini’s life of Jesus 1.28.14

I was fascinated. Here was someone who described himself as a believer — an Episcopalian, the denomination of my youth, no less — who spoke of Jesus and Christianity in terms of myth and metaphor rather than as some sort of rigid, literal reality. I wanted to see how he brought the seeming contradictions of belief and mythology together.

Unfortunately, the book itself does not quite live up to the promise of Parini’s conversation with Ashbrook, mainly because he tries to have it too many ways — starting with what it means to be a believer. “In its Greek and Latin roots,” he writes, “the word ‘believe’ simply means ‘giving one’s deepest self to’ something.” And he quotes St. Anselm: “For I do not seek to understand so that I may believe, but I believe so that I may understand.” To my way of thinking, that is putting the metaphorical cart before the metaphorical horse.

My principal unease with Parini, though, is that he writes about “remythologizing” Jesus without quite doing so. On the one hand, he suggests that the miracles Jesus performed and his resurrection are not meant to be taken literally. On the other, he does not rule out the possibility that they actually did happen. Parini doesn’t seem to think it matters all that much whether Jesus came back from the dead metaphorically or materially. Yet to me that’s the most important question.

I say that in full awareness of my own intellectual limitations. Like most people who were educated in a Western context, my thinking tends to be binary. My attitude toward religion is that it’s either literally true or it isn’t; and since it almost certainly isn’t, then it’s something I needn’t trouble myself with. Mind you, I have no patience for Christopher Hitchens-style atheism, and I’m intrigued enough by the whole notion of spirituality to attend a Unitarian Universalist church. But belief to me is a state of mind, based on provable facts, and not something I would give my “deepest self” to in the absence of such facts.

Still, there is much to recommend in Parini’s short biography. Parini is a warm and humane guide to the life of Jesus and the early roots of Christianity. He is especially valuable in explaining Jesus “the religious genius” who synthesized Jewish, Greek and Eastern ideas, especially in the Sermon on the Mount. Parini’s learned exploration of Jesus’ moral and spiritual teachings transcends the reality-versus-metaphor divide.

If you’re looking for answers, then “Jesus” is not for you. There are none, and Parini doesn’t pretend otherwise. But if you’re interested in a different way of thinking about Christianity, then Parini’s brief guide is a good place to start.

--Dan Kennedy; Media Nation; Myth, reality and Jay Parini’s life of Jesus 1.28.14

annika brockschmidt

Annika Brockschmidt is a freelance journalist, author, and podcast-producer who currently writes for the Tagesspiegel, ZEIT Online and elsewhere. Her second non-fiction book America's Holy Warriors: How the Religious Right endangers Democracy was published in German in October 2021 and was an immediate bestseller. She co-hosts the podcast "Kreuz und Flagge" ("Cross and Flag") with visiting professor at Georgetown University, Thomas Zimmer, which explores the history of the Religious Right.

Mike Johnson isn't your Average Christian Right Avatar - He's influenced by fringe movements Unfamiliar to Most Political Analysts

Who is Mike Johnson, the man with horn-rimmed glasses who managed to become Speaker of the House—something Steve Scalise, Jim Jordan and Tom Emmer all failed to do? And what does he have that the other three didn’t? Johnson comes off as polite, speaking into microphones rather than shouting into them, and he’s considered affable and friendly. He was also widely unknown even in Washington political circles until recently (when asked about Johnson, Republican Senator Susan Collins said she didn’t know who he was and would have to Google him first). There are however a small handful of political commentators who don’t have to Google Johnson to know who he is and what he stands for: Those who’ve been writing about White Christian nationalism in the US for years.

As many commentators have noted since his election as speaker, Mike Johnson has been an integral part of a movement that’s been sawing away at the democratic foundations of the country for decades: The Christian Right. But Johnson, like much of the Christian Right itself, is also profoundly influenced by fringe Christian thinkers and movements that few reporters and analysts of US politics are familiar with. (Annika Brockschmidt/Religion Dispatches 11/5/23)

Read More>>>>>

Who is Mike Johnson, the man with horn-rimmed glasses who managed to become Speaker of the House—something Steve Scalise, Jim Jordan and Tom Emmer all failed to do? And what does he have that the other three didn’t? Johnson comes off as polite, speaking into microphones rather than shouting into them, and he’s considered affable and friendly. He was also widely unknown even in Washington political circles until recently (when asked about Johnson, Republican Senator Susan Collins said she didn’t know who he was and would have to Google him first). There are however a small handful of political commentators who don’t have to Google Johnson to know who he is and what he stands for: Those who’ve been writing about White Christian nationalism in the US for years.

As many commentators have noted since his election as speaker, Mike Johnson has been an integral part of a movement that’s been sawing away at the democratic foundations of the country for decades: The Christian Right. But Johnson, like much of the Christian Right itself, is also profoundly influenced by fringe Christian thinkers and movements that few reporters and analysts of US politics are familiar with. (Annika Brockschmidt/Religion Dispatches 11/5/23)

Read More>>>>>

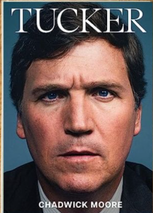

Tucker Carlson

Tucker Carlson is Wrong: Putin Practices Religious Persecution, Not Zelensky

Tucker Carlson recently claimed that Zelensky has “banned the Christian faith in his country and arrested nuns and priests.” Though purporting to speak on behalf of religious liberty, in reality Carlson is playing fast and loose with the truth and endangering the lives of Ukrainian believers. The Moscow-backed clergy being arrested in Ukraine are not neutral, but actively working for the Kremlin, some contributing directly to the deaths of hundreds of Ukrainian women and children. These arrests are not merely a whim of President Zelensky either: Eighty-five percent of Ukrainians polled favor the government taking action against these representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church who are causing mayhem in Ukraine—66 percent of Ukrainians want the Russian Orthodox Church banned completely in Ukraine. (Steven Moore/Tim Chapman/Providence 10/20/23)

Read More>>>>>

Tucker Carlson recently claimed that Zelensky has “banned the Christian faith in his country and arrested nuns and priests.” Though purporting to speak on behalf of religious liberty, in reality Carlson is playing fast and loose with the truth and endangering the lives of Ukrainian believers. The Moscow-backed clergy being arrested in Ukraine are not neutral, but actively working for the Kremlin, some contributing directly to the deaths of hundreds of Ukrainian women and children. These arrests are not merely a whim of President Zelensky either: Eighty-five percent of Ukrainians polled favor the government taking action against these representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church who are causing mayhem in Ukraine—66 percent of Ukrainians want the Russian Orthodox Church banned completely in Ukraine. (Steven Moore/Tim Chapman/Providence 10/20/23)

Read More>>>>>

Increasingly religious, Carlson holds that politics and work should be far in the back seat compared to faith and family, even declaring that “your work actually doesn’t mean very much, in the end.” Having grown up in such an atypical home, he always craved creating a close family and by all accounts has. For such a leading news media figure, it is remarkable that he not only lacks a social media account but does not even own a TV.

Being anchored to family and close friends has surely been a godsend to Carlson in light of what Moore paints as the mercilessly intolerant, cut throat world of News, Inc. In fact, within two days of making his first appearance on Carlson’s FOX program, the biographer was fired from his editor-at-large jobs at The Advocate and Out, perhaps America’s top gay publications. How revealing when Carlson points out that he continues to have “one friend who’s a personality at CNN,” yet “I can’t say this person’s name because it’ll wreck this person’s career.” --Dr Douglas Young; Libertarian Christian Institute; PORTRAIT OF A MAJOR MEDIA REBEL: A REVIEW OF TUCKER BY CHADWICK MOORE 9.11.23

Being anchored to family and close friends has surely been a godsend to Carlson in light of what Moore paints as the mercilessly intolerant, cut throat world of News, Inc. In fact, within two days of making his first appearance on Carlson’s FOX program, the biographer was fired from his editor-at-large jobs at The Advocate and Out, perhaps America’s top gay publications. How revealing when Carlson points out that he continues to have “one friend who’s a personality at CNN,” yet “I can’t say this person’s name because it’ll wreck this person’s career.” --Dr Douglas Young; Libertarian Christian Institute; PORTRAIT OF A MAJOR MEDIA REBEL: A REVIEW OF TUCKER BY CHADWICK MOORE 9.11.23

james carville

Dem Strategist Says Christians More Dangerous Than Terrorists

In a recent interview on HBO’s “Real Time with Bill Maher,” Democratic strategist James Carville, the “Ragin’ Cajun,” sparked controversy by asserting that Christian Republicans pose a greater threat to the United States than Islamic terrorists. Carville specifically targeted U.S. House Speaker Mike Johnson, alleging that his beliefs and affiliations are a fundamental danger to the nation. During the interview, Carville declared, “Mike Johnson and what he believes is one of the greatest threats we have today to the United States. This is a bigger threat than al-Qaeda to this country.” He went on to describe his perceived threat as ‘Christian nationalists,’ as a significant peril, claiming they have infiltrated key positions, including the Supreme Court.

(James Lasher/Charisma 12/5/23)

READ MORE>>>>>

In a recent interview on HBO’s “Real Time with Bill Maher,” Democratic strategist James Carville, the “Ragin’ Cajun,” sparked controversy by asserting that Christian Republicans pose a greater threat to the United States than Islamic terrorists. Carville specifically targeted U.S. House Speaker Mike Johnson, alleging that his beliefs and affiliations are a fundamental danger to the nation. During the interview, Carville declared, “Mike Johnson and what he believes is one of the greatest threats we have today to the United States. This is a bigger threat than al-Qaeda to this country.” He went on to describe his perceived threat as ‘Christian nationalists,’ as a significant peril, claiming they have infiltrated key positions, including the Supreme Court.

(James Lasher/Charisma 12/5/23)

READ MORE>>>>>

Political Strategist's Dire Warning About Mike Johnson

Democratic political strategist James Carville issued a dire warning on Friday about House Speaker Mike Johnson and what Christian nationalism could do to the United States. After Johnson, a Louisiana Republican, was elected as speaker in late October, questions arose about his political past. He has been accused of having strong ties to Christian nationalism, a movement that believes the United States is a solely Christian nation and that its laws and government should be focused on the religion's values. (Rachel Dobkin/Newsweek 12.2.23)

READ MORE>>>>>

Democratic political strategist James Carville issued a dire warning on Friday about House Speaker Mike Johnson and what Christian nationalism could do to the United States. After Johnson, a Louisiana Republican, was elected as speaker in late October, questions arose about his political past. He has been accused of having strong ties to Christian nationalism, a movement that believes the United States is a solely Christian nation and that its laws and government should be focused on the religion's values. (Rachel Dobkin/Newsweek 12.2.23)

READ MORE>>>>>

==sean hannity=================

With Turning Point Faith, Pastors Use Politics as a Church-Growth Strategy

His first stop was Godspeak Calvary Chapel of Thousand Oaks in California, headed by Pastor Rob McCoy, a former city council member and local mayor who had been a rising star in conservative evangelical circles during the early days of COVID-19. Under his leadership, Godspeak openly flouted California’s pandemic restrictions, holding in-person, maskless services that prompted a series of legal battles with county and state authorities. According to McCoy, Kirk helped land the pastor on Sean Hannity’s Fox News show to talk about his activism. As media attention grew, Godspeak’s attendance ballooned: far from dissuading churchgoers, COVID-related controversy only raised the church’s profile — and, according to multiple accounts, packed its pews. “We experienced 400% growth,” McCoy told Religion News Service in a recent interview.

McCoy said he encouraged other pastors to host Kirk, who lionized congregations that refused to close as garrisons against “tyranny,” a talking point that still shows up in Kirk’s stump speeches. Eventually, McCoy became co-chair of TPUSA Faith; “We play offense with a sense of urgency to win America’s culture war,” reads a tagline on a pamphlet distributed at TPUSA events.(Word & Way 6/12/23) READ MORE>>>>>

His first stop was Godspeak Calvary Chapel of Thousand Oaks in California, headed by Pastor Rob McCoy, a former city council member and local mayor who had been a rising star in conservative evangelical circles during the early days of COVID-19. Under his leadership, Godspeak openly flouted California’s pandemic restrictions, holding in-person, maskless services that prompted a series of legal battles with county and state authorities. According to McCoy, Kirk helped land the pastor on Sean Hannity’s Fox News show to talk about his activism. As media attention grew, Godspeak’s attendance ballooned: far from dissuading churchgoers, COVID-related controversy only raised the church’s profile — and, according to multiple accounts, packed its pews. “We experienced 400% growth,” McCoy told Religion News Service in a recent interview.

McCoy said he encouraged other pastors to host Kirk, who lionized congregations that refused to close as garrisons against “tyranny,” a talking point that still shows up in Kirk’s stump speeches. Eventually, McCoy became co-chair of TPUSA Faith; “We play offense with a sense of urgency to win America’s culture war,” reads a tagline on a pamphlet distributed at TPUSA events.(Word & Way 6/12/23) READ MORE>>>>>

==laura ingraham=============

Over 12K Sign Christian Petition Condemning 'False Prophet' Mike Johnson

In response to Mike Johnson recently becoming the new House speaker, over 12,000 people have signed a Christian petition condemning the congressman as a "false prophet" among other Republican Party members.

Faithful America, an online Christian group that supports social justice causes, released their second-annual "False Prophets Don't Speak for Me" campaign featuring a list of top Christian-nationalist leaders in both church and politics along with a petition on Tuesday. The list, which in addition to Johnson, identifies former President Donald Trump, pastor Mark Burns, self-proclaimed prophet affiliated with the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR) Julie Green, Fox News host Laura Ingraham, Ohio Representative Jim Jordan, conservative activist and radio talk show host Charlie Kirk, pastor Jackson Lahmeyer, Texas' Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, Archbishop Carlo Viganò, self-proclaimed prophet affiliated with NAR Lance Wallnau, and co-founder of Moms for Liberty and school board chair in Sarasota, Florida, Bridget Ziegler as "false prophets."

(Natalie Venegas/Newsweek 11/4/23)

Read More>>>>>

In response to Mike Johnson recently becoming the new House speaker, over 12,000 people have signed a Christian petition condemning the congressman as a "false prophet" among other Republican Party members.

Faithful America, an online Christian group that supports social justice causes, released their second-annual "False Prophets Don't Speak for Me" campaign featuring a list of top Christian-nationalist leaders in both church and politics along with a petition on Tuesday. The list, which in addition to Johnson, identifies former President Donald Trump, pastor Mark Burns, self-proclaimed prophet affiliated with the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR) Julie Green, Fox News host Laura Ingraham, Ohio Representative Jim Jordan, conservative activist and radio talk show host Charlie Kirk, pastor Jackson Lahmeyer, Texas' Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, Archbishop Carlo Viganò, self-proclaimed prophet affiliated with NAR Lance Wallnau, and co-founder of Moms for Liberty and school board chair in Sarasota, Florida, Bridget Ziegler as "false prophets."

(Natalie Venegas/Newsweek 11/4/23)

Read More>>>>>

dan kennedy

Dan Kennedy

Dan Kennedy

I listened to the podcast of “On Point” host Tom Ashbrook’s recent interview with the poet and author Jay Parini. The subject was Parini’s new book, “Jesus: The Human Face of God” (Icons).

I was fascinated. Here was someone who described himself as a believer — an Episcopalian, the denomination of my youth, no less — who spoke of Jesus and Christianity in terms of myth and metaphor rather than as some sort of rigid, literal reality. I wanted to see how he brought the seeming contradictions of belief and mythology together.

Unfortunately, the book itself does not quite live up to the promise of Parini’s conversation with Ashbrook, mainly because he tries to have it too many ways — starting with what it means to be a believer. “In its Greek and Latin roots,” he writes, “the word ‘believe’ simply means ‘giving one’s deepest self to’ something.” And he quotes St. Anselm: “For I do not seek to understand so that I may believe, but I believe so that I may understand.” To my way of thinking, that is putting the metaphorical cart before the metaphorical horse.

My principal unease with Parini, though, is that he writes about “remythologizing” Jesus without quite doing so. On the one hand, he suggests that the miracles Jesus performed and his resurrection are not meant to be taken literally. On the other, he does not rule out the possibility that they actually did happen. Parini doesn’t seem to think it matters all that much whether Jesus came back from the dead metaphorically or materially. Yet to me that’s the most important question.

I say that in full awareness of my own intellectual limitations. Like most people who were educated in a Western context, my thinking tends to be binary. My attitude toward religion is that it’s either literally true or it isn’t; and since it almost certainly isn’t, then it’s something I needn’t trouble myself with. Mind you, I have no patience for Christopher Hitchens-style atheism, and I’m intrigued enough by the whole notion of spirituality to attend a Unitarian Universalist church. But belief to me is a state of mind, based on provable facts, and not something I would give my “deepest self” to in the absence of such facts.

Still, there is much to recommend in Parini’s short biography. Parini is a warm and humane guide to the life of Jesus and the early roots of Christianity. He is especially valuable in explaining Jesus “the religious genius” who synthesized Jewish, Greek and Eastern ideas, especially in the Sermon on the Mount. Parini’s learned exploration of Jesus’ moral and spiritual teachings transcends the reality-versus-metaphor divide.

If you’re looking for answers, then “Jesus” is not for you. There are none, and Parini doesn’t pretend otherwise. But if you’re interested in a different way of thinking about Christianity, then Parini’s brief guide is a good place to start. --Dan Kennedy; Media Nation; Myth, reality and Jay Parini’s life of Jesus 1.28.14

I was fascinated. Here was someone who described himself as a believer — an Episcopalian, the denomination of my youth, no less — who spoke of Jesus and Christianity in terms of myth and metaphor rather than as some sort of rigid, literal reality. I wanted to see how he brought the seeming contradictions of belief and mythology together.

Unfortunately, the book itself does not quite live up to the promise of Parini’s conversation with Ashbrook, mainly because he tries to have it too many ways — starting with what it means to be a believer. “In its Greek and Latin roots,” he writes, “the word ‘believe’ simply means ‘giving one’s deepest self to’ something.” And he quotes St. Anselm: “For I do not seek to understand so that I may believe, but I believe so that I may understand.” To my way of thinking, that is putting the metaphorical cart before the metaphorical horse.

My principal unease with Parini, though, is that he writes about “remythologizing” Jesus without quite doing so. On the one hand, he suggests that the miracles Jesus performed and his resurrection are not meant to be taken literally. On the other, he does not rule out the possibility that they actually did happen. Parini doesn’t seem to think it matters all that much whether Jesus came back from the dead metaphorically or materially. Yet to me that’s the most important question.

I say that in full awareness of my own intellectual limitations. Like most people who were educated in a Western context, my thinking tends to be binary. My attitude toward religion is that it’s either literally true or it isn’t; and since it almost certainly isn’t, then it’s something I needn’t trouble myself with. Mind you, I have no patience for Christopher Hitchens-style atheism, and I’m intrigued enough by the whole notion of spirituality to attend a Unitarian Universalist church. But belief to me is a state of mind, based on provable facts, and not something I would give my “deepest self” to in the absence of such facts.

Still, there is much to recommend in Parini’s short biography. Parini is a warm and humane guide to the life of Jesus and the early roots of Christianity. He is especially valuable in explaining Jesus “the religious genius” who synthesized Jewish, Greek and Eastern ideas, especially in the Sermon on the Mount. Parini’s learned exploration of Jesus’ moral and spiritual teachings transcends the reality-versus-metaphor divide.

If you’re looking for answers, then “Jesus” is not for you. There are none, and Parini doesn’t pretend otherwise. But if you’re interested in a different way of thinking about Christianity, then Parini’s brief guide is a good place to start. --Dan Kennedy; Media Nation; Myth, reality and Jay Parini’s life of Jesus 1.28.14

charlie kirk

Over 12K Sign Christian Petition Condemning 'False Prophet' Mike Johnson

In response to Mike Johnson recently becoming the new House speaker, over 12,000 people have signed a Christian petition condemning the congressman as a "false prophet" among other Republican Party members.

Faithful America, an online Christian group that supports social justice causes, released their second-annual "False Prophets Don't Speak for Me" campaign featuring a list of top Christian-nationalist leaders in both church and politics along with a petition on Tuesday. The list, which in addition to Johnson, identifies former President Donald Trump, pastor Mark Burns, self-proclaimed prophet affiliated with the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR) Julie Green, Fox News host Laura Ingraham, Ohio Representative Jim Jordan, conservative activist and radio talk show host Charlie Kirk, pastor Jackson Lahmeyer, Texas' Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, Archbishop Carlo Viganò, self-proclaimed prophet affiliated with NAR Lance Wallnau, and co-founder of Moms for Liberty and school board chair in Sarasota, Florida, Bridget Ziegler as "false prophets."

(Natalie Venegas/Newsweek 11/4/23)

Read More>>>>>

In response to Mike Johnson recently becoming the new House speaker, over 12,000 people have signed a Christian petition condemning the congressman as a "false prophet" among other Republican Party members.

Faithful America, an online Christian group that supports social justice causes, released their second-annual "False Prophets Don't Speak for Me" campaign featuring a list of top Christian-nationalist leaders in both church and politics along with a petition on Tuesday. The list, which in addition to Johnson, identifies former President Donald Trump, pastor Mark Burns, self-proclaimed prophet affiliated with the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR) Julie Green, Fox News host Laura Ingraham, Ohio Representative Jim Jordan, conservative activist and radio talk show host Charlie Kirk, pastor Jackson Lahmeyer, Texas' Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, Archbishop Carlo Viganò, self-proclaimed prophet affiliated with NAR Lance Wallnau, and co-founder of Moms for Liberty and school board chair in Sarasota, Florida, Bridget Ziegler as "false prophets."

(Natalie Venegas/Newsweek 11/4/23)

Read More>>>>>

kathryn jean lopez

Kathryn Jean Lopez

Kathryn Jean Lopez

Christianity in Iraq, on the other hand, is in a different place, on the other side of the ISIS genocide that drove most of the Christians from Mosul to Erbil, near Kurdistan. When it comes to the persecuted Church, Iraq is a hopeful story, if a work in progress.

“ISIS is defeated, Christ is victorious,” Archbishop Bashar Warda tells me. “The Church is back again. Mass is back again.”

Warda, who established the exchange program with Franciscan University, says it has helped change how young Iraqis see Americans.

At first, many of his people thought the students coming to teach them must have been desperate for jobs. But as the Iraqis got to know the American teachers, they saw real faith, talent and generosity.

The young people are coming because “they want to serve the needs of the Church. They show the beauty and kindness of American Catholics,” Warda says.

During the genocide, Warda was able, with the help of the Knights of Columbus and Aid to the Church in Need, to establish a Catholic university and a hospital, among other things, for the people who wound up on his doorstep as refugees from ISIS.

He was able to help Christians see a future in Iraq — education for children and jobs for their parents. Warda credits good priests like then-Father (now Bishop) Thabet Habib Yousif Al Mekko for doing the difficult work of “accompanying his people through that long, painful road.” (Both Warda and Thabet were in Orlando for the annual Knights of Columbus convention this summer.)

This is no small thing. In 2014, Iraqi Christians understandably were tempted to think “this is the end ... That there is no future for them in Iraq,” Warda remembers. --Kathryn Jean Lopez; Press Republican; Christianity is alive and well in Iraq 9.18.23

“ISIS is defeated, Christ is victorious,” Archbishop Bashar Warda tells me. “The Church is back again. Mass is back again.”

Warda, who established the exchange program with Franciscan University, says it has helped change how young Iraqis see Americans.

At first, many of his people thought the students coming to teach them must have been desperate for jobs. But as the Iraqis got to know the American teachers, they saw real faith, talent and generosity.

The young people are coming because “they want to serve the needs of the Church. They show the beauty and kindness of American Catholics,” Warda says.

During the genocide, Warda was able, with the help of the Knights of Columbus and Aid to the Church in Need, to establish a Catholic university and a hospital, among other things, for the people who wound up on his doorstep as refugees from ISIS.

He was able to help Christians see a future in Iraq — education for children and jobs for their parents. Warda credits good priests like then-Father (now Bishop) Thabet Habib Yousif Al Mekko for doing the difficult work of “accompanying his people through that long, painful road.” (Both Warda and Thabet were in Orlando for the annual Knights of Columbus convention this summer.)

This is no small thing. In 2014, Iraqi Christians understandably were tempted to think “this is the end ... That there is no future for them in Iraq,” Warda remembers. --Kathryn Jean Lopez; Press Republican; Christianity is alive and well in Iraq 9.18.23

October 31, 2023:

Amanda Marcotte

Amanda Marcotte

(Mike) Johnson largely managed to keep his name out of the national news before his ascendance as the highest-ranking Republican on Capitol Hill. That's why he won, as Republicans hoped to conceal his far-right radicalism under the veil of ignorance. .....This is, after all, the same politician who once fought to secure taxpayer funding for a Noah's ark-based theme park. Yes, he did so out of a conviction that a literal flood wiped out all life on earth except that of an old man, his family, and a boatful of animals around 2300 B.C. Never mind that there is a historical record of thriving, well-documented civilizations like Mesopotamia and Egypt at the time, and they did not disappear into a flood. The Noah exhibit even claimed dinosaurs were on the ark, which did not stop Johnson from arguing that 'what we read in the Bible are actual historical events.'" --Amanda Marcotte; Salon

matt mcmanus

Matt Mcmanus

Matt Mcmanus

".....everyone hopes God is on Brandon Johnson’s side — and a statement of hope about the environment. And that wraps this meeting of the ecology reading group of the Institute for Christian Socialism — a name the political Right would locate somewhere between oxymoron and heresy.

The Institute for Christian Socialism (ICS), founded in the late 2010s by scholars and activists, is one of a growing number of left Christian organizations to emerge or be revived over the past decade, from radical Black churches to LGBTQ-affirming congregations. Stridently opposed to the right-wing approach to the Gospels, Christian leftists and socialists profess a radical faith centered on our duties to the least among us. Conventional wisdom suggests all forms of socialism share a bedrock commitment to atheistic materialism, following Marx’s infamous description of religion as the “opiate of the masses.” Less remembered is that, in context, Marx suggests religion is something like medicinal: it’s “the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions.” Many socialists agree with Marx’s dialectical take here, that one of religion’s major draws is how it makes sense of an unjust world. But to Christian socialists, religion isn’t merely consolation; it’s a profound call to action and good works. The roots of Christian socialism are in scripture itself. While conservative Christians view humanity as radically fallen — thus requiring the steady hand of tradition and authority to curb evil — Christian socialists turn that theology into an injunction against the corrupting influence of political and economic power. For Christian socialists, the equality of souls under God obligates us to care for the marginalized and vulnerable while guarding against domination. When Jesus declared that it’s easier for a camel to pass through the eye of the needle than for a rich man to enter heaven, or insisted that God stands with the “wretched of the earth” — the title of Frantz Fanon’s anti-colonial masterpiece — he laid the groundwork for Christian socialism. --Matt Mcmanus; In These Times; Christian Socialists Are Reclaiming Faith from the Right 9.18.23

The Institute for Christian Socialism (ICS), founded in the late 2010s by scholars and activists, is one of a growing number of left Christian organizations to emerge or be revived over the past decade, from radical Black churches to LGBTQ-affirming congregations. Stridently opposed to the right-wing approach to the Gospels, Christian leftists and socialists profess a radical faith centered on our duties to the least among us. Conventional wisdom suggests all forms of socialism share a bedrock commitment to atheistic materialism, following Marx’s infamous description of religion as the “opiate of the masses.” Less remembered is that, in context, Marx suggests religion is something like medicinal: it’s “the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions.” Many socialists agree with Marx’s dialectical take here, that one of religion’s major draws is how it makes sense of an unjust world. But to Christian socialists, religion isn’t merely consolation; it’s a profound call to action and good works. The roots of Christian socialism are in scripture itself. While conservative Christians view humanity as radically fallen — thus requiring the steady hand of tradition and authority to curb evil — Christian socialists turn that theology into an injunction against the corrupting influence of political and economic power. For Christian socialists, the equality of souls under God obligates us to care for the marginalized and vulnerable while guarding against domination. When Jesus declared that it’s easier for a camel to pass through the eye of the needle than for a rich man to enter heaven, or insisted that God stands with the “wretched of the earth” — the title of Frantz Fanon’s anti-colonial masterpiece — he laid the groundwork for Christian socialism. --Matt Mcmanus; In These Times; Christian Socialists Are Reclaiming Faith from the Right 9.18.23

Matt Mcmanus

Matt Mcmanus

When Jesus declared that it’s easier for a camel to pass through the eye of the needle than for a rich man to enter heaven, or insisted that God stands with the “wretched of the earth,” he laid the groundwork for Christian socialism..............The roots of Christian socialism are in scripture itself. While conservative Christians view humanity as radically fallen — thus requiring the steady hand of tradition and authority to curb evil — Christian socialists turn that theology into an injunction against the corrupting influence of political and economic power. For Christian socialists, the equality of souls under God obligates us to care for the marginalized and vulnerable while guarding against domination. When Jesus declared that it’s easier for a camel to pass through the eye of the needle than for a rich man to enter heaven, or insisted that God stands with the “wretched of the earth” — the title of Frantz Fanon’s anti-colonial masterpiece — he laid the groundwork for Christian socialism. --Matt Mcmanus; In These Times; 9.18.23

elon musk

With antisemitic tweet, Elon Musk reveals his ‘actual truth’

New York CNN — Elon Musk has publicly endorsed an antisemitic conspiracy theory popular among White supremacists: that Jewish communities push “hatred against Whites.” That kind of overt thumbs up to an antisemitic post shocked even some of Musk’s critics, who have long called him out for using racist or otherwise bigoted dog whistles on Twitter, now known as X. It was the multibillionaire’s most explicit public statement yet endorsing anti-Jewish views.(Allison Morrow /CNN 11/17/23)

READ MORE>>>>>

New York CNN — Elon Musk has publicly endorsed an antisemitic conspiracy theory popular among White supremacists: that Jewish communities push “hatred against Whites.” That kind of overt thumbs up to an antisemitic post shocked even some of Musk’s critics, who have long called him out for using racist or otherwise bigoted dog whistles on Twitter, now known as X. It was the multibillionaire’s most explicit public statement yet endorsing anti-Jewish views.(Allison Morrow /CNN 11/17/23)

READ MORE>>>>>

candace owens

The hijacking of ‘Christ is King’

What did Candace Owens mean when she posted that “Christ is King” in the midst of a very public dispute with her Daily Wire employer Ben Shapiro? I’m not going to enter into the details of that dispute other than to say I agree with Shapiro’s concerns. Here, I want to focus on Owens posting the words “Christ is King” on X (formerly Twitter). (Michael Brown/ Christian Post 11/20/23)

Read More>>>>>

What did Candace Owens mean when she posted that “Christ is King” in the midst of a very public dispute with her Daily Wire employer Ben Shapiro? I’m not going to enter into the details of that dispute other than to say I agree with Shapiro’s concerns. Here, I want to focus on Owens posting the words “Christ is King” on X (formerly Twitter). (Michael Brown/ Christian Post 11/20/23)

Read More>>>>>

jeanine pirro

Jeanine Pirro

Jeanine Pirro

".......look, this country was found on the Judeo-Christian ethics. We, you know, when I was the judge in my courtroom above my bench, it said “In God we trust.” I think that America is moving so far from that foundation that we are in a dangerous point that every person who is a person of religion or a person of God understands the inherent dangers of what is happening in America today.

We are flirting with the kind of destiny that only destroyed nations and fallen empires find themselves in. And so that's why I wrote the book Crimes Against America. What the left is doing to our children in schools and to Americans across the board, and especially to those believers, people who believed in God and are faith-driven, is it is destroying them.

And, you know, we saw it with the Dobbs decision. When our own Department of Justice would not follow its own rules of making an arrest of anyone who is parading or protesting in front of a Supreme Court justice’s home in the hope of getting them to change their opinion. Not one of those people was arrested, but you could rest assured that everyone, everyone who was involved in any way — and some of them who were clearly innocent and found to be not guilty by juries later — who got involved in any kind of pro-choice objection ended up being arrested and ended up being prosecuted.

But any of the pro-life centers or the pregnancy centers, any of the attacks on them were not even — they were not even investigated. And so, when you look at what is happening, the takedown of religion in America, it forebodes a very difficult future. And I think that people of faith need to worry about not just what's being taught in schools in terms of transgender nonsense, but what is happening in our society today against religion." --Jeanine Pirro; Flashpoint w/Pastor Gene Bailey May 30, 2023

We are flirting with the kind of destiny that only destroyed nations and fallen empires find themselves in. And so that's why I wrote the book Crimes Against America. What the left is doing to our children in schools and to Americans across the board, and especially to those believers, people who believed in God and are faith-driven, is it is destroying them.

And, you know, we saw it with the Dobbs decision. When our own Department of Justice would not follow its own rules of making an arrest of anyone who is parading or protesting in front of a Supreme Court justice’s home in the hope of getting them to change their opinion. Not one of those people was arrested, but you could rest assured that everyone, everyone who was involved in any way — and some of them who were clearly innocent and found to be not guilty by juries later — who got involved in any kind of pro-choice objection ended up being arrested and ended up being prosecuted.

But any of the pro-life centers or the pregnancy centers, any of the attacks on them were not even — they were not even investigated. And so, when you look at what is happening, the takedown of religion in America, it forebodes a very difficult future. And I think that people of faith need to worry about not just what's being taught in schools in terms of transgender nonsense, but what is happening in our society today against religion." --Jeanine Pirro; Flashpoint w/Pastor Gene Bailey May 30, 2023

==jen psaki=====================

==ben shapiro===================

The hijacking of ‘Christ is King’

What did Candace Owens mean when she posted that “Christ is King” in the midst of a very public dispute with her Daily Wire employer Ben Shapiro? I’m not going to enter into the details of that dispute other than to say I agree with Shapiro’s concerns. Here, I want to focus on Owens posting the words “Christ is King” on X (formerly Twitter). (Michael Brown/ Christian Post 11/20/23)

Read More>>>>>

What did Candace Owens mean when she posted that “Christ is King” in the midst of a very public dispute with her Daily Wire employer Ben Shapiro? I’m not going to enter into the details of that dispute other than to say I agree with Shapiro’s concerns. Here, I want to focus on Owens posting the words “Christ is King” on X (formerly Twitter). (Michael Brown/ Christian Post 11/20/23)

Read More>>>>>