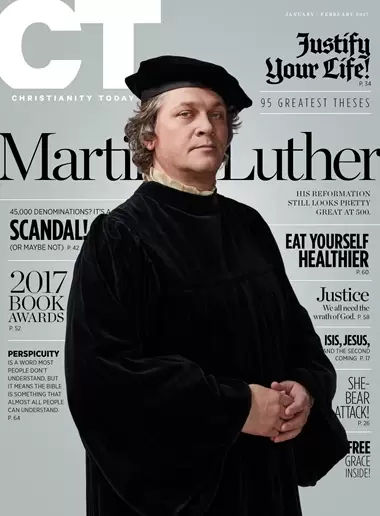

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (1483—1546) was a German theologian, professor, pastor, and church reformer. Luther began the Protestant Reformation with the publication of his Ninety-Five Theses on October 31, 1517. In this publication, he attacked the Church’s sale of indulgences. He advocated a theology that rested on God’s gracious activity in Jesus Christ, rather than in human works. Nearly all Protestants trace their history back to Luther in one way or another. Luther’s relationship to philosophy is complex and should not be judged only by his famous statement that “reason is the devil’s whore.”

May 3, 2023: Roys Report: Study Reveals Which Denominations Hold Strongest Beliefs on Tithing

The study released last week by Lifeway Research, a firm affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention, found that 77% of Protestant churchgoers in the U.S. affirm that “tithing is a biblical command that still applies today.” Only 10% rejected this belief and another 13% were unsure. Lutherans’ rejection of tithing “makes a lot of sense historically,” said David Croteau, dean of Columbia Biblical Seminary, commenting on the survey. “Martin Luther himself did not believe that Christians were required to tithe,” he told The Roys Report (TRR).

The study released last week by Lifeway Research, a firm affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention, found that 77% of Protestant churchgoers in the U.S. affirm that “tithing is a biblical command that still applies today.” Only 10% rejected this belief and another 13% were unsure. Lutherans’ rejection of tithing “makes a lot of sense historically,” said David Croteau, dean of Columbia Biblical Seminary, commenting on the survey. “Martin Luther himself did not believe that Christians were required to tithe,” he told The Roys Report (TRR).

Trevin Wax Files

Trevin Wax Files

Treating theologians as “all or nothing” isn’t the way to go. It’s not wise to tar and feather past theologians or uncritically embrace them. Sinful forebears still have something to teach us.

The impulse on social media is to put everyone in quick and easy boxes so we know instantly who the “heroes” and “villains” are, but real life is gloriously complicated. Some of those we might call “villainous” had heroic traits of virtue, while those we might call “heroes” had villainous streaks of sin.

Instead, looking deeper requires us to carefully reckon with sin’s distorting effects in the theological outlook of past theologians. Onsi Kamel recommends we “look at the specific loci of thought and the particular sin, and then investigate in particular how the thought was noticeably impacted by the sin. And then discount or warn about or treat carefully those dimensions of thought.”

We should wonder . . .

How did Luther’s vicious anti-Semitism affect his approach to the Old Testament? Did his view of the Jews shape his sharp distinctions between law and gospel or his two-kingdoms approach to society?

How did Edwards’s slaveholding affect his understanding of mercy and justice? How did it alter the way he understood the Bible or his view of God? How did it shape his view of how society is to be ordered or his doctrine of humanity? Does the fact Edwards’s son became an ardent abolitionist complicate these questions?

How might Barth’s adultery have influenced his views on sin and grace? Did his willful rebellion and theological gymnastics diminish his understanding of God’s judgment? Did they play a part in some of his semi-universalistic musings?

Sanctification is often uneven, and I understand if this article complicates the issue and stirs up more questions than answers. That’s why we need more debate about past theologians, not less. More complexity, not simplistic answers. Truth isn’t served by hagiography or exalted biographical sketches that minimize the sins of theologians from the past. Neither is truth served by the impulse to see only the sins and not the signs of sanctification in the lives of influential thinkers. --Trevin Wax; Gospel Coalition: Should We Cancel Karl Barth, Martin Luther, and Jonathan Edwards? 2.28.23

The impulse on social media is to put everyone in quick and easy boxes so we know instantly who the “heroes” and “villains” are, but real life is gloriously complicated. Some of those we might call “villainous” had heroic traits of virtue, while those we might call “heroes” had villainous streaks of sin.

Instead, looking deeper requires us to carefully reckon with sin’s distorting effects in the theological outlook of past theologians. Onsi Kamel recommends we “look at the specific loci of thought and the particular sin, and then investigate in particular how the thought was noticeably impacted by the sin. And then discount or warn about or treat carefully those dimensions of thought.”

We should wonder . . .

How did Luther’s vicious anti-Semitism affect his approach to the Old Testament? Did his view of the Jews shape his sharp distinctions between law and gospel or his two-kingdoms approach to society?

How did Edwards’s slaveholding affect his understanding of mercy and justice? How did it alter the way he understood the Bible or his view of God? How did it shape his view of how society is to be ordered or his doctrine of humanity? Does the fact Edwards’s son became an ardent abolitionist complicate these questions?

How might Barth’s adultery have influenced his views on sin and grace? Did his willful rebellion and theological gymnastics diminish his understanding of God’s judgment? Did they play a part in some of his semi-universalistic musings?

Sanctification is often uneven, and I understand if this article complicates the issue and stirs up more questions than answers. That’s why we need more debate about past theologians, not less. More complexity, not simplistic answers. Truth isn’t served by hagiography or exalted biographical sketches that minimize the sins of theologians from the past. Neither is truth served by the impulse to see only the sins and not the signs of sanctification in the lives of influential thinkers. --Trevin Wax; Gospel Coalition: Should We Cancel Karl Barth, Martin Luther, and Jonathan Edwards? 2.28.23

William Edgar Files

William Edgar Files

Indeed, redemptive history is sprinkled with great men and women who struggled at some point with deep discouragement and despair. A well-known example is Martin Luther (1483–1546), who had bouts with depression caused, for example, by contracting the bubonic plague in 1527, or, ironically, by the success of the Reformation and his doubts about his ability to guide it forward. He called such bouts anfechtung, “assaults” that threatened his convictions. Another example is Anne Bradstreet (1612–1672), the remarkable Puritan poet, who admitted to her children that she had traversed serious periods of doubt. “Many times hath Satan troubled me concerning the verity of the Scriptures,” she wrote in a letter she left them after she died. But she remained in the faith.

--William Edgar; Desiring God; The Faith Crisis of Francis Schaeffer 2.4.23

--William Edgar; Desiring God; The Faith Crisis of Francis Schaeffer 2.4.23

Simeon Zahl

Simeon Zahl

Luther described the situation of our own culture very well in his commentary on Psalm 51:

The Gentiles who are without the Word do not properly understand these evils even though they lie right in the middle of them … Thus they cannot properly evaluate any of human nature, because they do not know the source from which these calamities have come upon mankind.

In other words, Luther is saying we need to understand about sin because without it we will not be able fully to understand or describe the reality of the evils and sufferings we see around us. The Gentiles, Luther is saying, are like those who try to make sense of the cancer they are suffering from but don’t make use of the best diagnostic instrument available. Just read most political and social thinkpieces these days. No matter how intelligent or informed the writer, what is glaringly missing so often to a reader like me is a sense of sin. There is a naïve optimism about education or about human intentions or both, and a failure to recognize the basic bias against flourishing, which functions on both individual and societal levels. -Dr. Simeon Zahl ; The Doctrine of Sin; NYC Conference in 2016

The Gentiles who are without the Word do not properly understand these evils even though they lie right in the middle of them … Thus they cannot properly evaluate any of human nature, because they do not know the source from which these calamities have come upon mankind.

In other words, Luther is saying we need to understand about sin because without it we will not be able fully to understand or describe the reality of the evils and sufferings we see around us. The Gentiles, Luther is saying, are like those who try to make sense of the cancer they are suffering from but don’t make use of the best diagnostic instrument available. Just read most political and social thinkpieces these days. No matter how intelligent or informed the writer, what is glaringly missing so often to a reader like me is a sense of sin. There is a naïve optimism about education or about human intentions or both, and a failure to recognize the basic bias against flourishing, which functions on both individual and societal levels. -Dr. Simeon Zahl ; The Doctrine of Sin; NYC Conference in 2016

Martin Luther

Martin Luther

What does Christ mean when He says, “I will do whatever you ask in my name”? I would think He should say, “What you ask the Father in my name, he will do.” But Christ is pointing to Himself in this passage.

These are peculiar words coming from a human being. How can a mere man make such lofty claims? With these simple words, Christ clearly states that He is the true and almighty God, equal with the Father.

For whoever says, “Whatever you ask, I will do,” is saying, “I am God, Who can and will give you everything.” Why else should Christians pray in Jesus’ Name? Who do people call on saints as helpers in times of need?

Some call for Saint George for protection in War, Saint Sebastian for protection from pestilence, and others for other circumstances; obviously, they believe that these saints will somehow answer their prayers.

But Christ claims this role for Himself. In other words, He is saying, “I won’t command others to do whatever you ask for, I will do it Myself.” So He is the One Who can help in every situation with what we need.

He is mightier than the devil, sin, death, the world, and all creation. No being—whether human or angelic—has ever had, or ever will have, such power. Christ possesses all of God’s power and strength.

Here Christ sums up what we can ask Him for in prayer, He doesn’t limit His promise by adding, “That is, only if you ask for gold and silver or for something that other people can give you.”

Rather, He says that He will do “whatever you ask.” --Martin Luther

These are peculiar words coming from a human being. How can a mere man make such lofty claims? With these simple words, Christ clearly states that He is the true and almighty God, equal with the Father.

For whoever says, “Whatever you ask, I will do,” is saying, “I am God, Who can and will give you everything.” Why else should Christians pray in Jesus’ Name? Who do people call on saints as helpers in times of need?

Some call for Saint George for protection in War, Saint Sebastian for protection from pestilence, and others for other circumstances; obviously, they believe that these saints will somehow answer their prayers.

But Christ claims this role for Himself. In other words, He is saying, “I won’t command others to do whatever you ask for, I will do it Myself.” So He is the One Who can help in every situation with what we need.

He is mightier than the devil, sin, death, the world, and all creation. No being—whether human or angelic—has ever had, or ever will have, such power. Christ possesses all of God’s power and strength.

Here Christ sums up what we can ask Him for in prayer, He doesn’t limit His promise by adding, “That is, only if you ask for gold and silver or for something that other people can give you.”

Rather, He says that He will do “whatever you ask.” --Martin Luther

“The Christian shoemaker does his duty not by putting little crosses on the shoes, but by making good shoes, because God is interested in good craftsmanship.” ― Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther

“So when the Devil throws your sins in your face and declares that you deserve death and hell, tell him this: I admit that I deserve death and hell, what of it? For I know One who suffered and made satisfaction on my behalf. His name is Jesus Christ, Son of God, and where he is there I shall be also!” --Martin Luther

“So when the Devil throws your sins in your face and declares that you deserve death and hell, tell him this: I admit that I deserve death and hell, what of it? For I know One who suffered and made satisfaction on my behalf. His name is Jesus Christ, Son of God, and where he is there I shall be also!” --Martin Luther

March 10, 2010:

Inerrancy of Scripture

The Reformers similarly affirmed the truthfulness of the Bible. There is some debate among scholars whether Luther and Calvin limited Scripture’s truthfulness to matters of salvation, conveniently overlooking errors about lesser matters. It is true that Luther and Calvin are aware of apparent discrepancies in Scripture and that they often speak of “errors.” However, a closer analysis seems to indicate that the discrepancies and errors are consistently attributed to copyists and translators, not to the human authors of Scripture, much less to the Holy Spirit, its divine author. Calvin was aware that Paul’s quotations of the Old Testament (e.g., Romans 10:6 and Deuteronomy 30:12) were not always exact, nor always exegetically sound, but he did not infer that Paul had thereby made an error. On the contrary, Calvin notes that Paul is not giving the words of Moses different sense so much as applying them to his treatment of the subject at hand. Indeed, Calvin explicitly denies the suggestion that Paul distorts Moses’ words. (Kevin J. Vanhoozeron; CS Lewis Insttute)

Read More>>>>>

The Reformers similarly affirmed the truthfulness of the Bible. There is some debate among scholars whether Luther and Calvin limited Scripture’s truthfulness to matters of salvation, conveniently overlooking errors about lesser matters. It is true that Luther and Calvin are aware of apparent discrepancies in Scripture and that they often speak of “errors.” However, a closer analysis seems to indicate that the discrepancies and errors are consistently attributed to copyists and translators, not to the human authors of Scripture, much less to the Holy Spirit, its divine author. Calvin was aware that Paul’s quotations of the Old Testament (e.g., Romans 10:6 and Deuteronomy 30:12) were not always exact, nor always exegetically sound, but he did not infer that Paul had thereby made an error. On the contrary, Calvin notes that Paul is not giving the words of Moses different sense so much as applying them to his treatment of the subject at hand. Indeed, Calvin explicitly denies the suggestion that Paul distorts Moses’ words. (Kevin J. Vanhoozeron; CS Lewis Insttute)

Read More>>>>>

Feb 28, 2023: Gospel Coalition: Should We Cancel Karl Barth, Martin Luther, and Jonathan Edwards?

It was a jarring experience for me a couple years ago to encounter Christiane Tietz’s extraordinary biography of Karl Barth at the same time as I was reading books on how most of the church fathers approached the task of theology.

Barth is perhaps the most influential Christian theologian of the last century, rivaled only by Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI). And yet as hidden aspects of Barth’s life have come into the light, we now know he lived in an adulterous relationship with his assistant, Charlotte von Kirschbaum, and even arranged his living conditions around this sin, to the detriment of his wife, Nelly. What’s worse, he made twisted and bizarre theological justifications for persisting in unfaithfulness.

It was a jarring experience for me a couple years ago to encounter Christiane Tietz’s extraordinary biography of Karl Barth at the same time as I was reading books on how most of the church fathers approached the task of theology.

Barth is perhaps the most influential Christian theologian of the last century, rivaled only by Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI). And yet as hidden aspects of Barth’s life have come into the light, we now know he lived in an adulterous relationship with his assistant, Charlotte von Kirschbaum, and even arranged his living conditions around this sin, to the detriment of his wife, Nelly. What’s worse, he made twisted and bizarre theological justifications for persisting in unfaithfulness.

Feb 4, 2023: Desiring God: The Faith Crisis of Francis Schaeffer

Indeed, redemptive history is sprinkled with great men and women who struggled at some point with deep discouragement and despair. A well-known example is Martin Luther (1483–1546), who had bouts with depression caused, for example, by contracting the bubonic plague in 1527, or, ironically, by the success of the Reformation and his doubts about his ability to guide it forward. He called such bouts anfechtung, “assaults” that threatened his convictions. Another example is Anne Bradstreet (1612–1672), the remarkable Puritan poet, who admitted to her children that she had traversed serious periods of doubt. “Many times hath Satan troubled me concerning the verity of the Scriptures,” she wrote in a letter she left them after she died. But she remained in the faith.

Indeed, redemptive history is sprinkled with great men and women who struggled at some point with deep discouragement and despair. A well-known example is Martin Luther (1483–1546), who had bouts with depression caused, for example, by contracting the bubonic plague in 1527, or, ironically, by the success of the Reformation and his doubts about his ability to guide it forward. He called such bouts anfechtung, “assaults” that threatened his convictions. Another example is Anne Bradstreet (1612–1672), the remarkable Puritan poet, who admitted to her children that she had traversed serious periods of doubt. “Many times hath Satan troubled me concerning the verity of the Scriptures,” she wrote in a letter she left them after she died. But she remained in the faith.

Nov 25, 2022: Living Lutheran: A true thanksgiving; Martin Luther on giving thanks

“For all of this I owe it to God to thank and praise, serve and obey him.” With these words in his Small Catechism, Martin Luther concludes his paraphrase of the First Article of the Apostles’ Creed. The point is clear: We owe God thanks for all God gives to us.

But there is a trap here that we can easily fall into. Just because we ought to do something for God doesn’t mean we can do it—or, in Luther’s succinct language: “An ‘ought’ never implies a ‘can.’”

The problem with thanksgiving (let alone praise, service and obedience) is twofold. On the one hand, we try to turn it into a “must,” and we put on our smiley face and say thank you. Every time my Aunt Gladys gave me wool socks for Christmas, I was faced with the same dilemma: I had to write a thank-you note, but I wasn’t really thankful at all. Hypocritical thanksgiving is the very opposite of true thanks.

On the other hand, we imagine that we can manufacture true thanksgiving on our own, and we take credit for being thankful (or feel guilty when we aren’t). But this isn’t true thanksgiving either.

“For all of this I owe it to God to thank and praise, serve and obey him.” With these words in his Small Catechism, Martin Luther concludes his paraphrase of the First Article of the Apostles’ Creed. The point is clear: We owe God thanks for all God gives to us.

But there is a trap here that we can easily fall into. Just because we ought to do something for God doesn’t mean we can do it—or, in Luther’s succinct language: “An ‘ought’ never implies a ‘can.’”

The problem with thanksgiving (let alone praise, service and obedience) is twofold. On the one hand, we try to turn it into a “must,” and we put on our smiley face and say thank you. Every time my Aunt Gladys gave me wool socks for Christmas, I was faced with the same dilemma: I had to write a thank-you note, but I wasn’t really thankful at all. Hypocritical thanksgiving is the very opposite of true thanks.

On the other hand, we imagine that we can manufacture true thanksgiving on our own, and we take credit for being thankful (or feel guilty when we aren’t). But this isn’t true thanksgiving either.

Nov 11, 2022: Christian Institute: All for the glory of God

Doing the washing up pleases God, just like biblical preaching. In a similar vein, Luther (1483-1546) stressed that all work should be seen as a form of service to God – “not only the churches but also the home, the kitchen, the cellar, the workshop, and the field”.

Disposable nappies weren’t around in Luther’s day. One of his most challenging tasks as a husband was washing and changing his baby’s nappies. But for Luther this was an activity “adorned with divine approval”, despite the “stench”. When a father does this work “God, with all his angels and creatures, is smiling”.

Doing the washing up pleases God, just like biblical preaching. In a similar vein, Luther (1483-1546) stressed that all work should be seen as a form of service to God – “not only the churches but also the home, the kitchen, the cellar, the workshop, and the field”.

Disposable nappies weren’t around in Luther’s day. One of his most challenging tasks as a husband was washing and changing his baby’s nappies. But for Luther this was an activity “adorned with divine approval”, despite the “stench”. When a father does this work “God, with all his angels and creatures, is smiling”.

|

The very fact that Christ suffered for us, and through His suffering became a propitiation for us, proves that we are (by nature) unrighteous, and that we for whom He became a propitiation, must obtain our righteousness solely from God, now that forgiveness for our sins has been secured by Christ’s atonement. By the fact that God forgives our sins (only) through Christ’s propitiation and so justifieth us by faith, He shows how necessary is His righteousness (for all). There is no one whose sins are not forgiven (in Christ). — Martin Luther, Commentary on Romans (Grand Rapids, MI.: Kregel, 1976), 78 |

"If I profess with the loudest voice and clearest exposition every portion of the truth of God except precisely that little point which the world and the devil are at that moment attacking, I am not confessing Christ, however boldly I may be professing Christ. Where the battle rages, there the loyalty of the soldier is proved; and to be steady on all the battlefield besides, is mere flight and disgrace if he flinches at that point." -Martin Luther

What does Christ mean when He says, “I will do whatever you ask in my name”? I would think He should say, “What you ask the Father in my name, he will do.” But Christ is pointing to Himself in this passage.

These are peculiar words coming from a human being. How can a mere man make such lofty claims? With these simple words, Christ clearly states that He is the true and almighty God, equal with the Father.

For whoever says, “Whatever you ask, I will do,” is saying, “I am God, Who can and will give you everything.” Why else should Christians pray in Jesus’ Name? Who do people call on saints as helpers in times of need?

Some call for Saint George for protection in War, Saint Sebastian for protection from pestilence, and others for other circumstances; obviously, they believe that these saints will somehow answer their prayers.

But Christ claims this role for Himself. In other words, He is saying, “I won’t command others to do whatever you ask for, I will do it Myself.” So He is the One Who can help in every situation with what we need.

He is mightier than the devil, sin, death, the world, and all creation. No being—whether human or angelic—has ever had, or ever will have, such power. Christ possesses all of God’s power and strength.

Here Christ sums up what we can ask Him for in prayer, He doesn’t limit His promise by adding, “That is, only if you ask for gold and silver or for something that other people can give you.”

Rather, He says that He will do “whatever you ask.”

--Martin Luther

These are peculiar words coming from a human being. How can a mere man make such lofty claims? With these simple words, Christ clearly states that He is the true and almighty God, equal with the Father.

For whoever says, “Whatever you ask, I will do,” is saying, “I am God, Who can and will give you everything.” Why else should Christians pray in Jesus’ Name? Who do people call on saints as helpers in times of need?

Some call for Saint George for protection in War, Saint Sebastian for protection from pestilence, and others for other circumstances; obviously, they believe that these saints will somehow answer their prayers.

But Christ claims this role for Himself. In other words, He is saying, “I won’t command others to do whatever you ask for, I will do it Myself.” So He is the One Who can help in every situation with what we need.

He is mightier than the devil, sin, death, the world, and all creation. No being—whether human or angelic—has ever had, or ever will have, such power. Christ possesses all of God’s power and strength.

Here Christ sums up what we can ask Him for in prayer, He doesn’t limit His promise by adding, “That is, only if you ask for gold and silver or for something that other people can give you.”

Rather, He says that He will do “whatever you ask.”

--Martin Luther

| |

False Christians cannot understand what Jesus is saying in this verse. They wonder, “What kind of Christians are these people? They can’t do anything more than eat and drink, work in their homes, take care of their children, and push a plow. We can do all that and better.”

False Christians want to something different and special—something above the everyday activities of an ordinary person. They want to join a convent, lie on the ground, wear sackcloth garments, and pray day and night. The believe these works are Christian fruit and produce a holy life.

Accordingly, they believe that raising children, doing housework, and performing other ordinary chores aren’t part of a holy life. For false Christians look to the external appearances and don’t consider the source of their works—whether or not they grow out of the vine.

But in the passage this verse is taken from. Christ says that the only works that are good fruit are those accomplished by people who are first in Him and remain in Him. What true believers do and how they live are considered good fruit—even if these works are more menial than loading a wagon with manure and driving it away.

Those false believers can’t comprehend this. They see these works as ordinary, everyday tasks. But there is a big difference between a believer’s works and an unbeliever’s works—even if they do the exact same thing. For an unbeliever’s works don’t spring from the vine—Jesus Christ. That’s why unbelievers cannot please God (cf. Romans 8:1-17). These works are not Christian fruit. But because believer’s works come from faith in Christ, they are all the result of genuine faith

--Martin Luther, Faith Alone

False Christians want to something different and special—something above the everyday activities of an ordinary person. They want to join a convent, lie on the ground, wear sackcloth garments, and pray day and night. The believe these works are Christian fruit and produce a holy life.

Accordingly, they believe that raising children, doing housework, and performing other ordinary chores aren’t part of a holy life. For false Christians look to the external appearances and don’t consider the source of their works—whether or not they grow out of the vine.

But in the passage this verse is taken from. Christ says that the only works that are good fruit are those accomplished by people who are first in Him and remain in Him. What true believers do and how they live are considered good fruit—even if these works are more menial than loading a wagon with manure and driving it away.

Those false believers can’t comprehend this. They see these works as ordinary, everyday tasks. But there is a big difference between a believer’s works and an unbeliever’s works—even if they do the exact same thing. For an unbeliever’s works don’t spring from the vine—Jesus Christ. That’s why unbelievers cannot please God (cf. Romans 8:1-17). These works are not Christian fruit. But because believer’s works come from faith in Christ, they are all the result of genuine faith

--Martin Luther, Faith Alone

“The Lord’s reply is especially irksome, that the everyday routine works which people are commanded to do, namely, that they are to love God and the neighbor, supersede all other works, regardless of how they shine and glitter. The fact is, not only the Pharisees among the Jews, and the hypocrites under the papacy, have regarded human traditions as more important than God’s commandments; for there is a little monk that sticks in all of us from youth on. We, too, regard the ordinary works God has commanded as insignificant, but the special, diverse works done by the Carthusians, monks, and hermits, about which God has commanded nothing, as especially noteworthy.”

“However, our Lord God is averse to such distinction. He does not prefer one before another, nor does he exclude anyone from serving him, no matter how lowly he might be. Instead, he enjoins upon everyone to exercise love to God and his neighbor. Since God seeks nothing extraordinary from us and tolerates no distinctions, we must conclude that when a maid, who has faith in Christ, dusts the house her work is more pleasing in service to God than that of St. Anthony in the wilderness. That is Christ’s meaning here. This is the highest commandment: to love God and one’s neighbor. God is not concerned about the rules of the Franciscans, Dominicans, or other monks, but wants us to serve him obediently and love the neighbor. They may consider their monastic rules to be something wonderful and special, but before God they are nothing. The very highest, best, and holiest work is when one loves God and the neighbor, whether a person is a monk or nun, priest or layperson, great or small.”

“…We, therefore, must learn to think and answer like this: Not something extraordinary, but to love God and your neighbor, that is the best way of life! If I do that, I don’t have to be searching for another way. It is so very true that loving God and the neighbor is the greatest and best work, even though it appears to be so very ordinary and insignificant.”

Martin Luther, Luther’s Sermons, vol. 7, pages 75-6.

“However, our Lord God is averse to such distinction. He does not prefer one before another, nor does he exclude anyone from serving him, no matter how lowly he might be. Instead, he enjoins upon everyone to exercise love to God and his neighbor. Since God seeks nothing extraordinary from us and tolerates no distinctions, we must conclude that when a maid, who has faith in Christ, dusts the house her work is more pleasing in service to God than that of St. Anthony in the wilderness. That is Christ’s meaning here. This is the highest commandment: to love God and one’s neighbor. God is not concerned about the rules of the Franciscans, Dominicans, or other monks, but wants us to serve him obediently and love the neighbor. They may consider their monastic rules to be something wonderful and special, but before God they are nothing. The very highest, best, and holiest work is when one loves God and the neighbor, whether a person is a monk or nun, priest or layperson, great or small.”

“…We, therefore, must learn to think and answer like this: Not something extraordinary, but to love God and your neighbor, that is the best way of life! If I do that, I don’t have to be searching for another way. It is so very true that loving God and the neighbor is the greatest and best work, even though it appears to be so very ordinary and insignificant.”

Martin Luther, Luther’s Sermons, vol. 7, pages 75-6.