david a hollinger |

David A. Hollinger is a former President of the Organization of American Historians, and an elected member of the American Philosophical Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His nine books include Postethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism (1995, 2000, and 2006), Science, Jews, and Secular Culture (1996), After Cloven Tongues of Fire (2013), and Protestants Abroad (2017). He is Preston Hotchkis Profess of History Emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley.

David A Hollinger

David A Hollinger

What counts as Christianity in any given place depends on who’s got the franchise. The Christian project has taken a lot of different forms in the last 2,000 years. But the forms it takes depend on someone being able to build a critical mass of people willing to accept those forms as Christian. Whatever ideas, interests, and values they bring in from outside then define Christianity in that particular case. They get the franchise.

Why is this important? Well, a couple of weeks ago, Michael Gerson, a columnist for The Washington Post, who is anti-Trump and pro-evangelical, wrote that the enthusiasm for Trump among evangelicals misunderstands what Christianity is. His answer to this is to go back to Scripture: we have all these great quotes from Jesus, the Sermon on the Mount, and stuff like that. These passages are core to a liberal Protestant orientation, and Gerson says: “Well, this is what Christianity is.”

I rather like the kind of Christianity that Gerson is advocating. Still, he needs to come to grips with the historicity of the Christian project as a whole and with the historicity of its various versions.

There is no primal essence to Christianity that we can get to by looking at the Bible and comparing the ideas and practices of any particular group claiming to be Christian. The Bible consists of more than 30,000 versions written over several centuries by many different kinds of people. The notion that we can discover what true Christianity is by just looking at the Bible and seeing it somehow more clearly than other people have is a mystical, deeply anti-historical claim.

Americans cannot be reminded often enough, a point made by John Fea and other 19th-century historians, that many white Southerners believed that holding slaves and advocating for slavery was Christian. It was not something that they did despite their Christianity. It wasn’t in tension with their Christianity. It was a sign of their Christianity. These were smart, well-educated, multilingual, sophisticated people, and their view of Christianity accommodated human slavery.

So yes, Christianity is something that’s very malleable. Look at the history of Protestantism. You’ve got one group after another that fixates on one little piece of Scripture, and this turns out to be everything. What are the dynamics of baptism, for example? - David Hollinger; Public Seminar; Why Christianity and the Fate of American Democracy Are Intertwined 9.26.22

Why is this important? Well, a couple of weeks ago, Michael Gerson, a columnist for The Washington Post, who is anti-Trump and pro-evangelical, wrote that the enthusiasm for Trump among evangelicals misunderstands what Christianity is. His answer to this is to go back to Scripture: we have all these great quotes from Jesus, the Sermon on the Mount, and stuff like that. These passages are core to a liberal Protestant orientation, and Gerson says: “Well, this is what Christianity is.”

I rather like the kind of Christianity that Gerson is advocating. Still, he needs to come to grips with the historicity of the Christian project as a whole and with the historicity of its various versions.

There is no primal essence to Christianity that we can get to by looking at the Bible and comparing the ideas and practices of any particular group claiming to be Christian. The Bible consists of more than 30,000 versions written over several centuries by many different kinds of people. The notion that we can discover what true Christianity is by just looking at the Bible and seeing it somehow more clearly than other people have is a mystical, deeply anti-historical claim.

Americans cannot be reminded often enough, a point made by John Fea and other 19th-century historians, that many white Southerners believed that holding slaves and advocating for slavery was Christian. It was not something that they did despite their Christianity. It wasn’t in tension with their Christianity. It was a sign of their Christianity. These were smart, well-educated, multilingual, sophisticated people, and their view of Christianity accommodated human slavery.

So yes, Christianity is something that’s very malleable. Look at the history of Protestantism. You’ve got one group after another that fixates on one little piece of Scripture, and this turns out to be everything. What are the dynamics of baptism, for example? - David Hollinger; Public Seminar; Why Christianity and the Fate of American Democracy Are Intertwined 9.26.22

Mar 29, 2023: The Nation: Christianity’s Place in the Left and the Right

A conversation with historian David Hollinger about the rise of evangelicalism, the decline of mainline Protestantism, and if the country has truly become more secular.

A conversation with historian David Hollinger about the rise of evangelicalism, the decline of mainline Protestantism, and if the country has truly become more secular.

Tracing the rise of evangelicalism and the decline of mainline Protestantism in American religious and cultural life

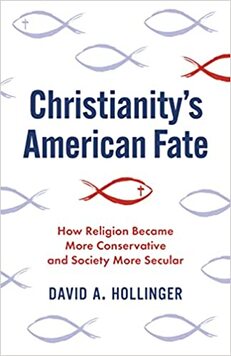

How did American Christianity become synonymous with conservative white evangelicalism? This sweeping work by a leading historian of modern America traces the rise of the evangelical movement and the decline of mainline Protestantism’s influence on American life. In Christianity’s American Fate, David Hollinger shows how the Protestant establishment, adopting progressive ideas about race, gender, sexuality, empire, and divinity, liberalized too quickly for some and not quickly enough for others. After 1960, mainline Protestantism lost members from both camps―conservatives to evangelicalism and progressives to secular activism. A Protestant evangelicalism that was comfortable with patriarchy and white supremacy soon became the country’s dominant Christian cultural force.

Hollinger explains the origins of what he calls Protestantism’s “two-party system” in the United States, finding its roots in America’s religious culture of dissent, as established by seventeenth-century colonists who broke away from Europe’s religious traditions; the constitutional separation of church and state, which enabled religious diversity; and the constant influx of immigrants, who found solidarity in churches. Hollinger argues that the United States became not only overwhelmingly Protestant but Protestant on steroids. By the 1960s, Jews and other non-Christians had diversified the nation ethnoreligiously, inspiring more inclusive notions of community. But by embracing a socially diverse and scientifically engaged modernity, Hollinger tells us, ecumenical Protestants also set the terms by which evangelicals became reactionary. (Princeton University Press - October 11, 2022)

How did American Christianity become synonymous with conservative white evangelicalism? This sweeping work by a leading historian of modern America traces the rise of the evangelical movement and the decline of mainline Protestantism’s influence on American life. In Christianity’s American Fate, David Hollinger shows how the Protestant establishment, adopting progressive ideas about race, gender, sexuality, empire, and divinity, liberalized too quickly for some and not quickly enough for others. After 1960, mainline Protestantism lost members from both camps―conservatives to evangelicalism and progressives to secular activism. A Protestant evangelicalism that was comfortable with patriarchy and white supremacy soon became the country’s dominant Christian cultural force.

Hollinger explains the origins of what he calls Protestantism’s “two-party system” in the United States, finding its roots in America’s religious culture of dissent, as established by seventeenth-century colonists who broke away from Europe’s religious traditions; the constitutional separation of church and state, which enabled religious diversity; and the constant influx of immigrants, who found solidarity in churches. Hollinger argues that the United States became not only overwhelmingly Protestant but Protestant on steroids. By the 1960s, Jews and other non-Christians had diversified the nation ethnoreligiously, inspiring more inclusive notions of community. But by embracing a socially diverse and scientifically engaged modernity, Hollinger tells us, ecumenical Protestants also set the terms by which evangelicals became reactionary. (Princeton University Press - October 11, 2022)

|

Oct 17, 2022

Christianity’s American Fate: How Religion Became More Conservative and Society More Secular The fate of the Christian project in any time and place depends on who holds the franchise. Evangelical Protestants wrested control from the rival, “mainline” Protestants by providing white Americans with a way to be counted as Christian while avoiding the challenges of an ethnoracially diverse society and a scientifically informed culture. The mainliners insisted Christians must face these challenges, even at the cost of enabling the growth of post-Protestant secularism and thereby diminishing Christianity’s size and public role. |

Mar 5, 2023

Puffin Interview Series with Dr. Joe Chuman: David A. Hollinger The Puffin Cultural Forum continues its monthly author interview series with Dr. Joe Chuman. David A. Hollinger’s “Christianity's American Fate: How Religion Became More Conservative and Society More Secular” traces the rise of evangelicalism and the decline of mainline Protestantism in American religious and cultural life. How did American Christianity become synonymous with conservative white evangelicalism? This sweeping work by a leading historian of modern America traces the rise of the evangelical movement and the decline of mainline Protestantism’s influence on American life. In Christianity’s American Fate, David Hollinger shows how the Protestant establishment, adopting progressive ideas about race, gender, sexuality, empire, and divinity, liberalized too quickly for some and not quickly enough for others. After 1960, mainline Protestantism lost members from both camps—conservatives to evangelicalism and progressives to secular activism. A Protestant evangelicalism that was comfortable with patriarchy and white supremacy soon became the country’s dominant Christian cultural force. |